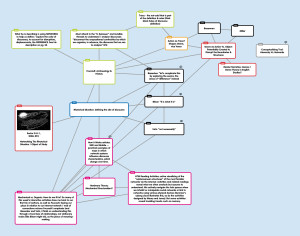

This week’s mind map exercise illustrates some overlap potential, but I have a sneaking suspicion that the organic nature of this network of ideas is developing a mind of its own.

My early efforts at mind mapping these connections are relying largely on key concepts of individual authors or activities. I notice, however, that the temptation is to begin arcing into mini-narratives – hardly suited to the limited space of this particular “genre.” There is simply so MUCH content to sift through, and trying to work within the rules of 2-D spatial limitations (design / color choices, creating sufficient white space, using concise terminology) is clearly becoming part of this network map’s constitution.

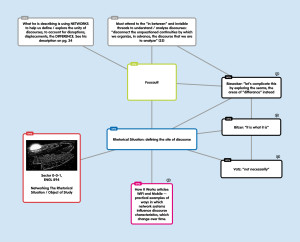

Based on our conversations of last week, Foucault’s thinking took on more clarity, enough that I was able to begin thinking through some possible connections — the basis of several of the new popplet entries. One of the more significant emerging threads is the possible connections between Foucault’s idea of Trace, the seen / not-seen in-between that has the power to define a discourse with as much (some like Bazerman might say more) power as the more traditional visible features (like grammar rules). So I began to wonder — in discussions of genre — whether we can see the Trace as Activity or as Bazerman puts it “enactment of social intentions” (“Systems of Genres” 75)? Bazerman and Foucault both comment on the reciprocal nature of the discourse (or genre) and the participants in same — Bazerman alludes to this on a cultural scale on pg. 325 of his “Speech Acts” article — in creative, connective, shaping powers. What might this mean on a disciplinary scale (I’m thinking of the current debates about online teaching and digital writing)?

Finally, thinking of the “master narratives” comment made in our last class, I began to wonder if past discussions of genre within English Studies (as an end it itself, typified by structural components or features alone rather than the alternative tools of analysis put forth this week by Miller, Bazerman, and Popham) constitute a Master Narrative of our discipline — if dominant theories created static, inflexible nodes. With the added layer of genre theory as described by Miller and Bazerman (and the scholars they cite) as well as Foucault’s archaeology, archives, and trace, can we now reflect upon our own discourse community’s history as one which performed through a model of “history of ideas”? And are we now moving confidently toward the more flexible “archaeologies of knowledge” thanks to interdisciplinary foci? But how do we navigate the presence of embedded inflexible nodes (such as theories and competing disciplines within our field — linguistics, composition, literary studies — that tend to foster a discourse of homogeneity (Foucault)? How do we “disrupt” the boundaries and structures in productive ways on a disciplinary as well as on a classroom scale? Certainly some unfinished thinking here, but as Foucault might say, understanding “discursive formation” is all about seeing it as a “space of multiple dissensions” (156) where analysis of the structure is not about the objects, but the tensions created by the activity, functions, relationships, and gaps.