Shaffer MOOC crib sheet

Introduction: In my first case study, I examined the Composition MOOC from the lens of structural theory, which provided a foundation upon which to build this second layer of analysis. There are a number of scholarly discussions concerning the technological “space” of MOOCs, including debates of access, politics of labor, and institutional economies. Those will not be the main focus of this case study, however, due to the limits of this project’s scope. Therefore, the second layer of analysis on which this study will focus reveals an area of tension and conflict that seems common to many discussions of Composition MOOCs: pedagogy.

This issue of pedagogy appears central to many debates over MOOCs, and especially for Composition. In her article “A Tale of Two MOOCs @ Coursera: Divided by Pedagogy,” Debbie Morrison argues that online classroom spaces are “transforming how people learn” and this “is driving the need for a new pedagogy” (emphasis mine). Morrison presents two case studies of MOOCs – one successful and one that was cancelled after only one week — offered by one of the leading platforms for educational MOOCs, Coursera. She asserts that one course failed because of its reliance on a pedagogy that had not adapted its methods to the characteristics that define the web space as a learning space. In particular, she argues that the failed course did so due to its reliance on a “learning model that most of higher education institutions follow – instructors direct the learning, learning is linear and constructed through prescribed course content featuring the instructor,” a method not unlike the way many face-to-face (f2f) Composition courses are conducted. Such methods, she argues, are unsuited for the ways in which the Web “as a platform for open, online, and even massive learning creates a different context for learning – one that requires different pedagogical methods.” If we accept this, then, as Porter suggests, “writing teachers will…have to change their fundamental thinking about teaching composition at the college level” (15). It is this premise that provides a framework for this analysis.

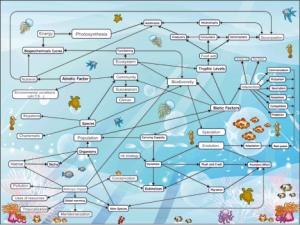

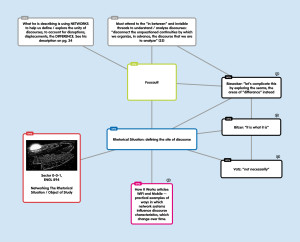

To this end, I have elected to focus on ways Genre Theory and Activity Theory may be used to illuminate, complicate, or obfuscate the field’s discussion of Composition MOOCs in terms of pedagogy, represented by the work of selected scholars integrated directly into the analysis. Morrison explores pedagogy in terms that are at times reminiscent of Genre Theory, but by highlighting the “variables common” to each course’s design (e.g., course platform, start and end dates), clear influences of Activity Theory may be seen as well. The elements of Genre Theory set forth by Bazerman, Miller, and Popham — in particular the concepts of classification, motives, and systems located in action (Miller 75) — productively draw attention to several key boundaries (or tensions). Especially important are assumptions made about learners and learning (what we might call “motives”) that inform teaching pedagogy. The online space and design of MOOC platforms, as well as assessment and delivery practices, may differ significantly from traditional f2f classrooms, depending on the course. If we explore these differences in terms of genre, these boundaries become sites of “contradiction” upon which to focus this analysis (Halasek et al.).

First, not all MOOCs are created equal. Design features and functions vary, so there is a risk in applying theories to this OoS as if the object is static. Decker defines two of the most prominent forms of MOOCs: xMOOC and cMOOC. The cMOOC is “based on distributed learning and connectivism” described as focusing “on knowledge creation and generation” (4). The xMOOC design “leans towards [theories of] Behaviorism and use more conventional instructor-centered delivery methods” such as “automated grading” (4). Fortunately, Composition pedagogy is a rather consistent node among ongoing networks of debate concerning the role of MOOCs in higher education in that our field’s (ideal) methodology seems well suited to the networked, student-centered learning models advanced by proponents of MOOCs. In fact, Dave Cromier (an early MOOC designer and proponent) asserts that knowledge in a MOOC is actually “an ecosystem from which knowledge can emerge,” a description that lends itself to alignment with the NCTE “Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing” that is key to our current Composition classroom practice and pedagogy (WPA “Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition”).

[http://youtu.be/bWKdhzSAAG0]

However, pedagogy itself – whether discussed in terms of practice or ideological moorings – is a complicated and vast expanse with a wide-ranging history of debate. Therefore, the purpose of this study is not to justify or discourage using MOOCs for teaching Composition, but to locate key nodes and borders upon which these theories may play a productive and illuminating role for those who are assessing MOOCs as a space for teaching freshman Composition.

How Theories Define This Study

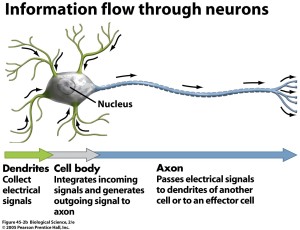

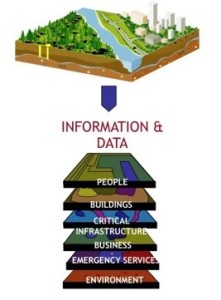

Activity Theory: Spinuzzi’s articulation of Activity Theory’s characteristics provides a useful starting point to begin outlining key areas in which to analyze Composition MOOCs and pedagogy. Current Composition theorists prioritize collaborative, process-based, and student-centered learning as underlying motives for classroom design. However, how to best implement such priorities is a subject of much debate within the field. Scholarly publications highlight this range; from WAC, to vertical writing curriculum design, to the role of reading (specifically concerning literature as primary texts for teaching), how such learning takes place can be discussed productively in terms of networks. As such, networks imply the presence of nodes of activity, connectivity, and interactivity. Examining Composition pedagogy in these terms allows us to examine the border between f2f and online MOOC course environments using Activity Theory principles and vocabulary.

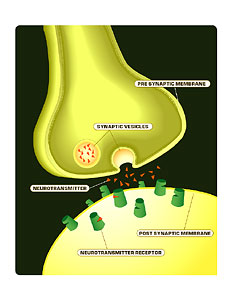

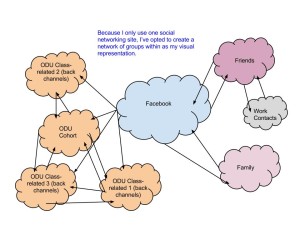

Characteristic #1: In his article, “How Are Networks Theorized,” Spinuzzi defines Activity Theory (AT) as “a theory of distributed cognition” that “focuses on issues of labor, learning, and concept formation” (62). Further, this theory continues to evolve, moving “from the study of individuals and focused activities to the study of interrelated sets of activities” (62) – networks that may include collaborative learning and development, both of which play significant roles in Composition pedagogy and MOOC structural designs. Such concepts and terms create a framework with which to explore how using a network lens provides a means with which to locate this discussion in terms of borders. As Morrison observes, the nature of a MOOC space does not easily align with the nature of an f2f classroom space. While the basic principles of Composition pedagogical theory must ground both in terms of the aforementioned priorities of student learning (as outlined by the NCTE in “Beliefs About the Teaching of Writing”), the nature of the space – the networks that represent the physical, the theoretical, and what AT calls the “dialectical” qualities of that space – create tensions at those boundaries which represent how to implement that learning. Morrison refers to the importance of “connectivism” as a corollary to “social constructivism,” a thread woven into modern pedagogical theory that states “students learn more effectively” when they are actively involved in knowledge construction that includes their own knowledge bases. Porter’s “Framing Questions About MOOCs and Writing Courses” suggests that if we are to critically assess MOOCs as a space where we teach freshman Composition, we must be critically aware of the design of the space, as well as the “toolbox of [instructional] methods” employed (14). He also highlights the importance of recognizing the differing networks of students who enroll in MOOCs as “a broader audience than simply campus-resident students…in relatively small classes…or via 1-on-1 tutorial consultations” (14).

Characteristic #2: Further, such activities require interaction and, according to the dialectical underpinnings that characterize AT, constitute a means of analysis that relies on a “‘science of interconnections’” (Spinuzzi “Networks” 69) to reveal the importance of networks to development or (in the case of pedagogy) learning. Such interactivity, then, leads to change or growth as a result of operating within a system of activity, one which allows for participants to bring “their own internal rules and expectations as well as external relations with other activity systems” into an operationalized framework (Spinuzzi “Networks” 79). This allowance for individual experiences and/or cultures to become a valued part of the learning environment creates an opportunity for “boundary crossing” if we see the role of instructor no longer limited to the teacher of record. Indeed, in some Composition MOOCs, the common pattern of teacher/node-to-student/node of activity relationships is transformed, much like Spinuzzi describes users innovating to make a space better serve users’ needs (Tracing Genres). Analysis such as Spinuzzi’s can affect information design – including pedagogy and activity networks (course designs) of MOOC or f2f class setting. Halasek et al. describe how the initial course design for their second semester FYC sequence as a MOOC was based on traditional f2f pedagogies, or what they called “grand pedagogical narratives” of “a central doxological status” (157). As they began to modify the course, they created new pathways or activity system that transformed the roles students and teachers played as students began to take on increasingly “teacher-ly” roles as peer readers and co-facilitators in Discussion Boards (158-9). This increase in connectivity that takes place in a MOOC are principles that every teacher of a FYW course who prioritizes peer workshop would acknowledge is a key component of classroom pedagogy.

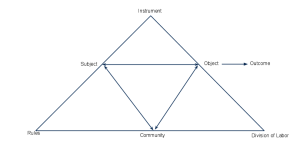

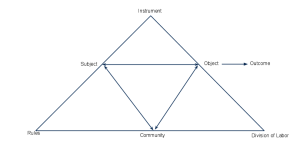

Spinuzzi, Activity System, p. 71

“How Are Networks Theorized”

Characteristic #3: [Spinuzzi Triangle Diagram Insert} Activity Theory as distributed cognition incorporates mediation as a key concept. Described by Spinuzzi as “tools, rules, and divisions of labor” (71), mediators are used by individuals within an activity system to “transform a particular object with a particular outcome in mind” in a way that is meaningful and connected to a (discourse) community (71-72). Composition MOOCs as networks are often seen through the filter of traditional f2f structural limitations, leading to concerns such as those described by Halasek et al., who assert that reflecting on “the MOOC learning environment” reveals the “ways we understood – and sometimes failed to understand – our roles as teachers of composition and our students’ roles as writers and learners” (156). Again, the example of the Discussion Boards serves as an example of how Activity Theory allows us to productively analyze the MOOC environment. Halasek et al. observe that Discussion Forums are typically conceptualized as nodes in which student participants depend on the “controlled exhanges…shaped and guided by teachers…and oriented toward assignment expectations” (159). In effect, these learning nodes are mediated in specific ways by a limited number of people who occupy academically hierarchical positions with relation to the student-to-teacher activity pathways. In the revised iteration of their MOOC class, Halasek et al. discovered that students “actively occupied” these learning spaces and mediated the activity as well as the flow of content when they “engaged and even tested the faculty team by making their needs explicit and articulating the problems the instructional context posed” (159). Such meta-participation is then makes students the mediators who transform the learning environment through their activity and co-creating of the space.

Characteristic #4: AT involves “chained activity systems,” a concept that may account for the sort of “organizational…boundaries” that create “informal linkages” between activities that could be interpreted as metacognitive nodes where transfer takes place (Spinuzzi “Networks” 74-77). For Composition, such metacognitive transfer has become an increasingly foregrounded concept in discussions of student writing. In MOOC spaces, this feature of AT becomes especially productive as a way to analyze it as a potentially viable mediator of student writing. Porter’s concerns about MOOC spaces appears centered on the nature of the systems in which learning / teaching take place. He argues that the frame of reference used to classify what is a Composition course is one area of tension in our field’s discussions of MOOCs. This feature then becomes a shared focal point or bridge that links to the second theory of analysis.

Genre Theory: Bazerman and Miller effectively lay out the foundational elements of Genre Theory, while Popham provides helpful principles of practical application. In fact, Popham’s concept of border genres effectively frames a means of exposing the instructional “belief systems …that determine the pedagogical methods selected for instruction” in courses, both MOOC and classroom based (Morrison). If we interpret pedagogy as a genre / border, the classroom space – f2f or MOOC – becomes a network of activity within which we might conceptualize and theorize participants (who occupy both learning and instructional roles at various times), assessment practices, media, and even the genre itself as nodes within that network that can become sites of closer analysis. There are several characteristics of genre theory, but for now, I will apply two primary features to this discussion of MOOCs.

Characteristic #1: Bazerman asserts that we must correct the enculturated habit of seeing a genre as just a set of features (322). This contention is reiterated by Porter, Decker, Morrison, Halasek et al., and others who argue that MOOCs cannot simply be treated as a mere duplication of f2f Composition classroom pedagogy. For example, in their article “Digital Genres: A Challenge to Traditional Genre Theory,” Askehave and Neilsen draw heavily from Swales’ seminal work in genre theory to advance the argument that any discussion of digital learning spaces must include an “up-grade[d]…genre model” that incorporates the element of media. Further, they argue that the terms “genre” and “medium” are often conflated, obscuring the importance of “the borders between the two” as distinctive areas of analysis. They assert that such conflation occurs when characteristics of digital spaces push the limits of traditional text-bound frameworks for understanding and studying genre. This leads to the observation that “media is not only a distribution channel but also a carrier of meaning, determining … social practices [such as] how a text is used, by whom it is used, and for what purpose” (138). Such observations demonstrate the productive potential of applying genre theory to this analysis of Composition MOOCs in terms of revealing key assumptions that drive not only the definition of “genre” but pedagogical ideologies as well. They also raise a question of separation, one which exposes yet another border tension common in discussions of MOOCs in our field: should we teach a Composition MOOC exactly the same way as we teach a f2f Composition class? This is a question that intersects this analysis on points of pedagogy in terms of genre or form as well as activity and agency.

Characteristic #2: Bazerman and Miller add the feature of exigence or motives to their expanded definition of genres. These factors allow us to think of delivery and interpretation (Miller) as ways of discussing participants in networks. When we consider Spinuzzi’s description of activity theory as “the study of interrelated sets of activities” (Tracing Genres 79), the networked nature of a MOOC seems to be a perfect object of examination using this lens to clarify relationships and hierarchies in terms of what Spinuzzi calls “sociotechnical networks” that create spaces for “distributed cognition” (62). Thus, the need to push past a concept of genre that creates a monolithic frame of “the thing” may be transformed and its usefulness for digital spaces expanded when we integrate users’ / participants’ / designers’ motives in terms of “the role of individuals in using and making meaning” (Bazerman 317). As Miller points out, genres should be seen as a way to accomplish tasks and not simply as a form (151). Therefore, if we see the activity nodes as part of this work, the relationships between nodes in this activity system become an integral part of the pedagogy, and a marker of both pedagogy and MOOCs as potential genres. For a MOOC space, this highlights many of the contradictions or tensions of the boundary created between the f2f genre of composition pedagogy and that employed in effectively designed MOOCs.

Legend, map of Iraq 1970

When combined with Activity Theory, highlighting as I believe it will the importance of a networked conception of learning in MOOC spaces, exploring this object of study as a genre may open new possibilities to theorize pedagogies and classroom design. In fact, it is my assertion that this analysis suggests it may become fruitful to see modern Composition pedagogy as a genre that has evolved as our field has evolved, taking on canonical status within our field as theories of practice replace others in terms of dominance. Just as Prior et al.’s argument for “remapping the rhetorical canon” using a variation of activity theory (CHAT) is based on the boundary between print text-mediated ideologies and those informed by the evolution of digital media, our fields’ discussions of MOOC-based Composition pedagogy may require a bit of remapping as well. Genre and Activity Theories may provide the legend (or map key) for this endeavor.

Chris Friend illustrates the usefulness of such an approach in his blog post entitled, “Will MOOCs Work for Writing?” Friend argues that while “[w]e cannot teach all students every intricacy of writing…using a MOOC format, …we can use MOOC strategies to improve our existing in-class teaching efforts.” In a more strongly worded assessment of interpreting the MOOC as part of a genre system, he writes that “MOOCs force a paradigm shift in pedagogy as we consider education in different contexts and at different scales.” His list of “five essential MOOC philosophies that can be applied to face-to-face instruction” echoes Miller’s theory of genres as one that incorporates a social discourse dimension.

However, there is a danger here, one that genre theory illuminates: when we conflate MOOCs with other forms of online education, or see MOOCs as “one size fits all,” we highlight a site of tension common to studies of MOOCs. Friend’s assertion that MOOC practices can actually enhance – but not replace — f2f Composition classroom pedagogy is suggestive of Popham’s theory of boundary genres (283), in which the activity or action locates the site of analysis, typically embodied in an artifact of some sort. Popham’s focus is on forms shared between a medical community network and the insurance / business community network as part of the medical practice ecology. If we interlace elements of activity theory that examine “interrelated sets of activities” (Spinuzzi “Networks” 62), it is also possible the boundary form may become the pedagogy itself. Each boundary suggests a system of networks in play, carrying with them “influence” and “relations” (Popham 280) that stem from the social discourses and expectations described by Miller’s three-level model: pragmatic (action) + syntactic (form) + semantic (substance of the “cultural life”) (Miller 68). This model highlights the nature of relationships inherent not only between theories but in their analysis as well.

Nodes & Agency: Relationships Defined & Transformed by Theories

Both Activity Theory as defined by Spinuzzi and Bazerman’s System of Genres are particularly helpful frameworks when theorizing Composition MOOCs as networks in terms of the relationship between nodes and agency. In their article, Halasek et al. argue that MOOCs are currently analyzed through two “grand pedagogical narratives” that create a system of “doxological status” informing such analysis. In these forms, the instructor and student occupy defined hierarchial positions, or nodes, with the teacher in the dominant knowledge-delivery role. The pedagogy of a more traditional f2f Composition classroom platform created by this model then serves as the “dominant hierarchical genre form” used to analyze all alternatives (157). Halasek et al. see these as “entrenched narratives” that “rigidly define the respective roles of teacher and student alike, making it difficult to imagine alternative learning dynamics” (157). Given the overlaid network of academic institutional histories, such systematized pedagogy may be read as part of a larger system that may be useful for mapping the “pathways” (Bazerman 99) or networks of learning as well as instructional design in any analysis of MOOCs as an object of study.

Spinuzzi applies Activity Theory in terms of connected activity systems in which mediators – which in this case may be the digital space itself, the technology, or the pedagogical system that functions as a genre – provide the “tools, rules, and division of labor” (71) to create a system suited for “distributed cognition” (69). With respect to Halasek’s argument, Spinuzzi’s characterization of “contradictions” as “engines of change” and transformation (a key component of Activity Theory) becomes a means of considering the impact of designers’ pedagogies as well as the agency afforded users in this learning space.

The most obvious nodes discernible in a network-theorized classroom such as a Composition MOOC are the participants (students, tutors, and instructors), as well as the means of mediating the connections between them: the technology itself. Such articulations of nodes function similarly whether seen through a lens of Activity Theory or Genre Theory. For example, by classifying participants as nodes of activity, pedagogical considerations driven by a student-centered learning environment are revealed to function along lines common to social constructivism, emphasizing collaborative features but also “cognitive orientations” of the pedagogy informing course structure (Morrison). If this “cognitive orientation” mirrors that of a writing course in which the instructor-to-student hierarchy of delivery is dominant, Genre Theory may prove effective as a means of identifying characteristics of that pedagogical style which informs the direction and function of network connectivities. If, on the other hand, the nodes are connected in multiple, non-hierarchical ways — such as the student-to-student group learning or embedded tutor-to-student conferencing described by Halasek — such characteristics reveal a pedagogy at work that may create sufficient differentiation that would require we examine Composition MOOC spaces as a separate genre within a larger system of Composition education. Such framing might lend credence to arguments that these cMOOC designs validate their place in higher education as a manifestation of the possibilities born of extended application of our notions of the student-centered theory of writing pedagogies.

Image from “MOOCs From the Student Perspective” Pepper Lynn Warner

Aside from the human participants engaged in this classroom network system, activities such as, writing, writing assessment, and collaboration can also be explored as nodes as well as sites of movement with the MOOC space. The forms they take are heavily influenced – as is true with any genre – by the dominant classification system at work. The pedagogy, if we accept this as a type of genre, dictates not only the participants or agency at each node but also what tools will mediate this activity. In the case of a Composition MOOC, the platform-as-node influences the means of writing and assessment. However, the pedagogy-as-genre will be reflected in these nodes and the relationships between nodes. For example, in a cMOOC, multiple layers of assessment are made possible by the non-hierarchical nature of the teaching model. Students and embedded tutors may be part of the assessment process, as well as the teacher of record (Decker 7). The dominant role of peer review in a typical f2f Composition classroom is expanded in ways mediated by the open, massive digital space of a MOOC. Such design is mediated further by the pedagogically-driven choices by the class designer – the instructor. However, student input driven by navigational habits may be interpreted as influential agency in determining the network activity and nodal importance.

However, there are tensions which cannot be so easily mitigated by framing MOOCs in this way. Friend’s article demonstrates some of the risks revealed by applying genre theory to discussions of Composition MOOCs, particularly in terms of pedagogies. Friend argues that “we can use MOOC strategies to improve our existing in-class teaching efforts” tends to conflate the two spaces, perhaps running the risk of narrowing this discussion into nostalgic frames. While his suggestions may at first glance legitimize the composition MOOC by validating its pedagogical methods as potential “levers” (Bazerman 79), it also exposes a controversial border space in which both Morrison and Porter situate their arguments. Such “space to space” transference points to the argument made by Glance, Forsey, and Riley that a conflation of these genres creates additional tensions in discussions of pedagogy, or what they refer to as “the potential disruptive nature of MOOCs.” They write, “A difficulty with the analysis of MOOC structure and its pedagogical foundations is the question of how similar a MOOC is to existing online courses offered for distance learning or as an extension of face-to-face delivery of courses as part of a so-called blended delivery. In some ways they are not and so the analysis of MOOCs is inherently not that different from research examining the benefits of online delivery of courses generally.” Therefore, even if we treat pedagogy as part of a genre system, there still remains the question of transfer when it comes to the “massive” environment of MOOCs.

Networks & Distribution of Content: Meaning In Motion

Askehave and Nielsen assert that the multi-dimensional nature of the WWW promotes the argument that “the medium forms an integral part of the genre and should be” considered as an important part of any analytical model (128-9). Mapping paths within this networked medium used to distribute content or meaning-making (inherent to any discussion of pedagogy) raises the question of how MOOC spaces affect not only the relationships between participants but activities as well. If we accept the premise that everything is moving in the network that is a MOOC – student identities, navigation, student compositions, collaborative energy, instructions, links to materials, assessments and feedback – does the network alter this content or meaning in substantial ways that can be usefully theorized? Some Composition MOOCs, like the one taught at Duke University, crowdsource feedback and assessment to some degree. Bazerman’s observation that we consider systems of activity as a way to “identify a framework which organizes…work, attention, and accomplishment” (319) might be used to consider not only the MOOC as a networked space but also activities such as assessment and collaboration using such features as crowdsource response and Discussion Boards. The “Massive” quality of MOOCs significantly complicates the Composition practices as well as the pedagogy, but if we think how activities might be located at carefully constructed nodes that create parcels of space, a system within a system, would that mitigate this concern? Bazerman explains that a “genre system” focuses “on what people are doing and how texts help people do it, rather than on texts as ends in themselves” (319). The problem arises when we see a genre (like pedagogy or like the Composition classroom space) as just a collection of features, that “makes it appear that these features of the text are ends in themselves, that every use of a text is measured against an abstract standard of what correctness to the form rather than whether it carries out the work it was designed to do” (Bazerman 323). In the Composition classroom envisioned by most of our field’s scholarship on pedagogical issues, this work is process- and feedback-dependent. Yet, Activity Theory encourages us to see activities in terms of “modular configuration[s] of work” (Spinuzzi Tracing Genres 75). In a cMOOC, roles of student and instructor (and pedagogy) are transformed due to the nature and demands of the space upon the ways these “nodes” interact.

Digital Humanities Course Page, University of South Carolina

Conclusion: Activity and Genre Theories are productive lenses through which to examine the ways we might explore Composition MOOCs as pedagogically informed spaces. What these two theories do not allow me to explore is the very real impact played by technology itself in terms of exerting agency, mediating behaviors, and user navigation (whether in the formalized role of student or teacher) in the same way that Actor Network Theory might have allowed. However, seeing the technology as a mediating tool may fit more cleanly into discussions of pedagogy, providing a familiar node from which the conversation can proceed and evolve. Technology does play a role in transforming the way we read, the way we think, and the way we teach – the question becomes one of degree. Activity Theory foregrounds the movement, the relationships, and the connectivity of a network, perhaps neglecting the power of those elements that make activity possible – things like space itself.

What these two theories do allow me to explore is the motivation that shapes the choices a learner or a teacher makes in terms of transmission (knowledge, assessment, identity). Both lend themselves powerfully to pragmatic applications of pedagogy. If we accept Miller’s observation that genres must be “grounded in the conventions of discourse” (67), then in the case of a Composition MOOC, we must consider another system may be at work, another type of discourse that is native to online spaces. Miller asserts that genres change as cultures change, leading us to treat genres as “cultural artifact[s]” (69). Along these lines, can we approach pedagogy as a genre as well – and thereby as “cultural artifact” (Miller 69) – wherein our theories of Composition pedagogy become the determining forms of practice, static no matter what the space? When defined as “reproducible,” a genre should certainly carry over from space to space; and perhaps some features of Composition pedagogy do (for example, collaborative networking, activity- and student-centered classroom practices). Yet a MOOC is not the sort of f2f classroom envisioned by our field’s discourse community by any stretch of the imagination, which raises the question of whether a different genre of pedagogy is required when analyzing this Object of Study. Should we, like Prior et al. suggest, “remap the canon” of Composition pedagogy to account for the “contradictions” (Spinuzzi, “How” 72) created by that space? Should we treat pedagogy as exigence because it must be more than “form or event” and be seen as “social action” (Miller 164)? Such questions may remain unanswered until our field can avoid conflating many of the nodes of this discussion – what Porter refers to as “a dangerous elision” (16) – which are used to define or frame the nature of a MOOC as a space for learning. Some argue it is a platform of materials, “an object to be bought and sold as if it were a textbook” (Porter 17). Others argue that all MOOCs are defined as if all share a common delivery focus, yet as Porter observes, there are significant differences between xMOOCs and cMOOCS which can be described in terms of motivation and nodes of interactivity (Activity Theory) or in terms of applying a universalized “formalist frame” (Genre Theory) to generate a framework for analysis (25). For all of these reasons, it is clear that these pedagogical / conceptual borders and related tensions are far from being resolved. Popham’s concept of boundary forms may offer a fruitful next step forward in this discussion. By treating cMOOCs as a genre whose boundaries often create sites of contention in discussions of Composition pedagogy, Popham’s strategies for “crossing boundaries” begins with locating “recognizable commonality of certain elements” like form (284). It may be that applying these two theories fulfill Popham’s recommended triplet of Translation, Reflection, and Distillation (284) to create a useful bridge over which we may navigate such boundaries in future discussions of the place of MOOCs in Composition. Theoretical lenses such as Genre and Activity Theories offer valuable framing devices with which to move such discussions forward — a necessary direction given the suggestion that MOOCs may not be a “fad” that we can easily dismiss.

Works Cited

Askehave, Inger and Anne Ellerup Nielsen. “Digital Genres: A Challenge to Traditional Genre Theory.” Information Technology & People 18.2 (2005): 120-141. Web. 28 Feb. 2014.

Bazerman, Charles. “Speech Acts, Genres, and Activity Systems: How Texts Organize Activity and People.” What Writing Does and How It Does It. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004. 309-339.

Cormier, Dave. “Knowledge in a MOOC.” YouTube Video, 2010.

Decker, Glenna L. “MOOCology 1.0.” Invasion of the MOOCs: The Promise and Perils of Massive Open Online Courses. Eds. Steven D. Krause and Charles Lowe. Anderson, SC: Parlor Press, 2014.

Friend, Chris. “Will MOOCs Work for Writing?” Hybrid Pedagogy. 28 Mar. 2013. Web. 28 Feb. 2014.

Glance, David George, Martin Forsey, and Myles Riley. “The Pedagogical Foundations of Massive Open Online Courses.” First Monday 18.5. 6 May 2013. Web. 5 Feb. 2014.

Halasek, Kay, Ben McCorkle, Cynthia L. Selfe, Scott Lloyd DeWitt, Susan Delagrange, Jennifer Michaels, and Kaitlin Clinnin. “A MOOC With A View: How MOOCs Encourage Us to Reexamine Pedagogical Doxa.” Invasion of the MOOCs: The Promise and Perils of Massive Open Online Courses. Eds. Steven D. Krause and Charles Lowe. Anderson, SC: Parlor Press, 2014.

Levine, Alan. “A MOOC or Not a MOOC: ds106 Questions the Form.” Invasion of the MOOCs: The Promise and Perils of Massive Open Online Courses. Eds. Steven D. Krause and Charles Lowe. Anderson, SC: Parlor Press, 2014.

Miller, Carolyn. “Genre As Social Action.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 70 (1984): 151-167.

Morrison, Debbie. “A Tale of Two MOOCs @ Coursera: Divided by Pedagogy.” Online Learning Insights: A Blog about Open and Online Education. 4 Mar. 2013. Web. 3 Mar. 2014. <http://onlinelearninginsights.wordpress.com/2013/03/4/a-tale-of-two-moocs-coursera-divided-by-pedagogy>

Popham, Susan. “Forms as Boundary Genres in Medicine, Science, and Business.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication 19 (2005): 279.

Porter, James. “Framing Questions About MOOCs and Writing Courses.” Invasion of the MOOCs: The Promise and Perils of Massive Open Online Courses. Eds. Steven D. Krause and Charles Lowe. Anderson, SC: Parlor Press, 2014.

Prior, Paul, Janine Solberg, Patrick Berry, Hannah Bellwoar, Bill Chewning, Karen J. Lunsford, Liz Rohan, Kevin Roozen, Mary P. Sheridan-Rabideau, Jody Shipka, Derek Van Ittersum, and Joyce Walker. Re-situating and Re-mediating the Canons: A Cultural-Historical Remapping of Rhetorical Activity. Kairos 11.3 (2007). Web. 14 Feb. 2014.

Spinuzzi, Clay. “How Are Networks Theorized?” Network: Theorizing Knowledge Work in Telecommunications. NY: Cambridge UP, 2008. 62-95.

Spinuzzi, Clay. Tracing Genres through Organizations: A Sociocultural Approach to Information Design. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003.