http://popplet.com/app/#/1571354

So, I puzzled over how to reconceptualize a mindmap 15 weeks in the making using concepts, rather than components. I reviewed our class syllabus for footholds, pondered my case study foci, watched a little ESPN on a break, checked the Red Sox score, and then (you see this coming, don’t you?)…

It’s beautiful, really — but like the game itself is rough around the edges (just look at the recent ejection of a pitcher for “hiding” pine tar on his neck). But, bear with me, let’s see how this metaphor plays out.

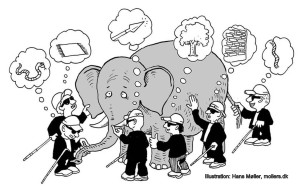

Coming up with the bases for this diamond was fairly simple: Pitcher’s mound = Operationalizing Theory, our course initiator. Whether through blogs or assigned asynchronous activities, it seemed we were all swinging away … at first a fast ball (How it Works, Rhetorical Theory), then a curve ball (Foucault), and even an occasional knuckle ball (Prior, Guattari). Thinking next of First Base = Nodes and Agency. Here is our first task, our first accomplishment, our first move into the field of play. Identifying the lineup, determining who’s on first, what’s on second, and on third? (Abbot & Costello say it best.) Here’s where the analogy gets a little squirrely, however; the deeper we went into the game (some might say into extra innings), the lineup and rotation changes. Suddenly, we’re talking about genre as not just a border but having agency, even distributing knowledge. (It seemed so simple when I started.)

On to Second Base = Connections & Communication. We were often asked in our case studies to address the question “What’s moving in the network? How are nodes situated? Describe the nature and directions of the relationships formed.” Again and again, we reshuffled the roster, trying out new combinations, looking for that “sweet spot” of theory to create a FrankenTheory that captured the complexity of our objects of study (dare I say, a pennant?). One of our final readings this term was concerned with Operating Systems, which — come to think of it — captures agency, nodes, movement, and signals for so many of the theorists and readings we covered. So, take a base.

Third Base = Meaning & Knowledge … nearly home. Our network theories always already involved knowledge. Whether it was in terms of creating or distributing, all of our theorists and practitioners (ourselves included) touched this base. You may notice I repeated a node here — the OS makes another appearance. Those kinship patterns — cultural discourse, ways of knowing, ways of learning — have to be embedded here, as well as back at 2nd base. And, wouldn’t you know it, 1st base as well. That’s the power of an ecological system — there’s material transfer happening all over the place.

At last, Home Plate = Why theory? It’s why we came to the park in the first place. I saw this as both the goal of the course, but a destination too. It’s where I locate myself as a scholar, and a practitioner. And true to any baseball game, it isn’t just the bases that matter. It isn’t even the players. We can’t complete this mindmap without widening the reach of this network to include those fans, the “10th man.” This is where we write our Case Studies, add new theoretical layers, toss out uncooperative ones. This is where we find the ecology of our field, where the game really becomes interesting.

Extra innings? Double header? Maybe next time. Right now, I think it’s time for the 7th inning stretch.