Composition MOOCs: Theorizing Pedagogy, Space, and Learning.

Why Here? Why Now? As argued in earlier case studies, the Composition MOOC is one of many different types of course offerings in an emerging trend (some would call it a fad) of online higher education. This is a site of considerable tension in our field of Composition studies, perhaps because many scholars see this as a step backward and away from the hard-won push for smaller-sized, learner-centered classrooms for freshman writing courses. Some of the most common concerns expressed by scholars and practitioners in our field about MOOCs are as follows:

- They will “devalue the current education system” (Friend).

- They will “disrupt” the same (Friend).

- MOOCs are a “lightning rod for virtually all that thrills and ails contemporary higher education” (Mitrano).

- They are simply another step in the commodification of higher education (Barlow).

- By that same token, “college leaders” see MOOCs as the competition, as MOOCs are – by nature – “open” and free of charge (“”What You Need to Know About MOOCs”).

- They are anonymous and diffused, thus threatening the teacher/student relationship.

- They foster or are founded on wrong-headed teaching practices.

- They threaten the role of and need for teachers.

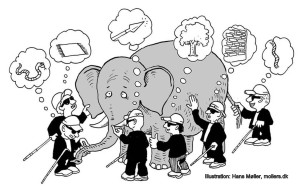

- They turn teachers into mere “content developers” (Gardner).

Yet, there are other scholars in our field who argue that these digital spaces can, with careful attention to the space’s design, exemplify best-practice models of collaborative learning and scaffolded teaching practices found to be so productive in a face-to-face (f2f) first-year composition (FYC) course (Decker, Cormier, Downes, Hart-Davidson, Bourelle et al.). Some have even gone so far as to argue that many of the criticisms err by conflating MOOC classroom pedagogy design with higher education operations in general (Cormier, Gardner). This discussion reflects our field’s cautious approach to MOOCs in the spirit of Cynthia Selfe’s counsel on “the importance of paying attention” when it comes to 21st century technology literacies. As well, the debate itself seems to emerge from a common paradigm: the place-anchored classroom, one that often limits the “node-load” of a network to a basic binary structure of teacher-learner. However, as this semester’s case studies have demonstrated, a Composition MOOC encompasses a much broader scale of elements: it is a networked space filled with nodes and agencies that emerge from not only the basic system of learning (teacher to student), but ecologies of other systems as well (institutional, assessment, collaborative relations between students independent of teacher directives, software, texts, etc.). As such, when current theories of networks are applied to MOOCs, they are often done so as if all MOOC classroom designs are the same. As Decker points out, this is most certainly not the case (4). Indeed, some Compositionists argue that our field should consider a refreshed pedagogy for learning spaces like MOOCs (Debbie Morrison’s “A Tale of Two MOOCs”). The assertion is that traditional f2f methods and technologies cannot be simply overlaid onto such a complex system / space with any hope of success.

Be that as it may, this final case study is not intended to be an argument for or against Composition MOOCs. Rather, using key threads gleaned from the theories of Spinuzzi, Foucault, Bateson’s and Gibson’s ecologies, and Neurobiology, it is my intention to theorize the potentiality of such space by highlighting key areas of tension in the current debate.

Thread 1: Foucault’s attention to “unities of discourse” provides an open door through which to begin mapping an amalgamation of theory, and serves as the premise by which this theory will address the question of “why this / why now?” Put another way, Foucault’s concepts of gaps, hierarchies, systems, and traces are the elemental glue that holds this FrankenTheory partnership together, calling our attention to those theoretical areas of dissonance that often go unmapped (traces). Foucault’s rejection of a linear, universalist lens by which to explore networks of knowledge pushes at what often appears to be a primacy of Composition Pedagogy Theory (situated in an f2f paradigm) in many of the aforementioned tensions when it comes to MOOCs and English Studies. In essence, his theory establishes a primer for this FrankenTheory, as he defers to a concept of a web — of influences and events (a network) — as a more “realistic” way to see and explore knowledge and knowing (3). Indeed, he asserts that we must see knowledge in terms of a complex system through a lens defined by terms he uses to explain statements as nodes. He proposes a more productive network is not a stable system, but one of complexity and discontinuities which have the power to transform current theoretical frameworks (5). Foucault allows that his “notion of discontinuity… is both an instrument and an object of research” (9), and for this reason becomes what amounts to a genomic element to this attempt to create new theory for examining both the Composition MOOC and theories currently infusing the discourse.

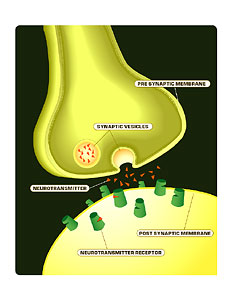

Thread 2: The field of Neurobiology contributes to this discussion in several important ways. First, as a metaphor, it frames the concepts of knowledge and learning in productive ways that can be extended into discussions of ecologies and complex activity systems, as well as the nature of discourse in technologically mediated / created spaces. The neuronal network mapping metaphor provides interesting ways with which to discuss learning and knowledge transfer within a networked system much like a classroom space. It also provides our field with a concrete look into the physiological network that is at the very heart of any learning space: the brain. Learning theories grounded in behavioral / psychology theories are all rooted in this central processing unit; considering the biomechanical processes situates the conversation in a way that moves the more theoretical and ontological discussions back into the realm of “how and where” of learning. Neurobiology, then, allows us to look at the potentiality for knowledge transfer in terms of “how” learners learn. However, the biomechanical will only move the discussion so far; the messiness of a “massive” system composed of many students from varying backgrounds, differently motivated, in many places, and mediated by diverse technologies may push a neurobiology-based metaphor beyond its limits. Alone, it is limited. Combined with these other threads of theory and operationalization, it becomes an important conceptual layer for discussions of the “how.”

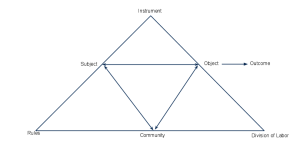

Thread 3: Spinuzzi’s Activity Theory contributes in two important ways: (1) distinctive terminology that begins to move our focus from the biomechanical to the relational and (2) as a pragmatic illustration of complex systems operationalized. His work with Actor-Network Theory and Activity Theory illustrates the power of Foucault’s gaps and disruptions when seeking common borders at which this conversation can turn. For example, Spinuzzi points to the gaps of “designer vs. user,” which in turn can productively correlate to a Composition MOOC’s gap / borders between instructor vs. student participant. Further, Spinuzzi’s use of distributed cognition (Activity Theory) and interconnections maps onto MOOC spaces in potentially useful ways, particularly when focusing on “interrelated sets of activities” (such as those described in Downes’ description of a connectivist course) rather than the individual learner, or networked minds vs. an individual mind (62). MOOC classroom models vary widely, earning such monikers as xMOOC and cMOOC, the latter of which has been deemed most effective by several scholars due to its emphasis on coordinated collaborative networking (Downes, Cormier). As scholars and compositionists, we must remain critically aware of the design of the learning / teaching spaces we employ / deploy, and Spinuzzi’s discussion of mediation and mediators provides a means with which to explore these. Spinuzzi’s Activity Theory allows our focus to center on concrete nodes of activity within a system: where and how the participants interact (where the learners learn and connect).

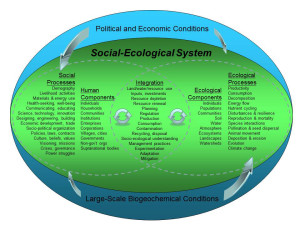

Thread 4: Ecology Theory deals exclusively with complex systems, not classroom spaces. However, the potential for mapping a dynamic and complex “living” network of actors, boundaries, and affordances as described by Bateson and Gibson is one of the more productive connections for MOOC discussions.Given the mechanics of the numerous digital platforms and software needed to operationalize a learning/teaching classroom space, it is not surprising to see so many critiques of MOOCs more in line with Hardware Theory, focusing on the mediating structures, than Learning Theory. Bateson and Gibson provide a counterweight to such limitations by attending to the power of boundaries to serve as both frontiers as well as informational economies (Bateson 467). Ecology Theory can thus extend our focus upon a classroom system to a larger scale, allowing me to discuss systems within systems. As proof of this usefulness, Margaret Syverson takes an ecological systems’ approach to the subject of the Composition classroom on the premise that a student’s “process of composing” – i.e., learning – takes place within a dynamic “complex system” based squarely upon ecological principles (Syverson 2-3).

The networked nature of complex systems and the affordances of web technology-based classrooms create a discursive space where each of these theories find play. Building upon Foucault’s concept of traces and gaps, each of these threads serves as both lens and map for examining the nodes and networks that comprise MOOC learning spaces, as well as highlighting the misfits or gaps. Further, each of these theoretical lenses at some point hinges upon the concept of “relationships,” a key component for distributed cognition as well as collaborative, workshop-based FYC theories of pedagogy. Finally, each of these theories provide the means by which to explore collaborative learning as both node and activity, a step which may contribute to the design of future cMOOCs and shape the nature of English Studies.

In sum, exploring this Object of Study using such a FrankenTheory may allow our field to address not only those concerns listed above but others like them, utilizing a network theory that may offer an appropriately complex lens to account for and grapple with the complexity of emerging digital learning, teaching, and theorizing spaces. The design of this synthesis falls into three broad sections, each based on significant questions that seem to lie at the heart of our field’s treatment of MOOCs: (1) knowledge and learning (or, “what does it mean to know?”), (2) the locus or framework of learning (or “how does location shape learning?”), and (3) agency (“who has it and why does that impact the discourse?”).

Baseline Concept: Knowledge and Learning

The concepts of knowledge and learning are key to this attempt to create a viable synthesis using these four theories, becoming an effective organizing principle with which to explore how these theorists give shape or problematize integration into a new theory of networks. Of particular worth is how these theories align and diverge in terms of the theorists’ framing of the terms and how, once synthesized, they become a useful tool with which to describe Composition MOOCs.

First, spaces in which knowledge is acquired and disseminated are shaped by premises that undergird what we mean when we consider the term knowledge as a thing to be constructed and transferred. David Cormier asserts that in traditional models of online courses that base their knowledge delivery system on a one-to-many model, it is the institution or the instructor who possess the knowledge desired by the students. In their original design, MOOCs constitute “an ecosystem from which knowledge can emerge” as a result of “negotiation”… a nod toward their roots in Vygotsky and the “social nature of learning” (Downes “Connective Knowledge”). From this perspective, it is not enough to use the term “knowledge” as a Composition classroom’s outcomes. Rather, the term “connective knowledge” emerges, pointing to a “gap” in Composition discourse where a network-based FrankentTheory might prove useful.

The field of neurobiology describes the function of the human brain as a communications network that first “takes in sensory information” via neurons, then “process[es] that information between neurons” as thinking, with the end result or response described in terms of neuronal “outputs” (“Neurobiology”). In other words, knowledge, as treated by neurobiology, is to some degree a byproduct of neurotransmitter activity transferring electrical and chemical impulses that create memories (in essence, knowing a thing). However, the network system – and in particular relationships within that system — in which such processes take place are just as important to how we understand knowledge creation, or learning. Synaptic connections operate on a cause-effect basis, transmitting data in one direction over a gap between neuronal structures. It is important to note that these “synapses are not merely gaps but … functional links between the two neurons” (“Neurobiology”). Foucault might say that these synaptic gaps – like black holes – are significant areas of scrutiny because of their functional nature. The entire “communication infrastructure” in which these neurons exist, however, are not the origin of the process.” Rather, the process that occurs within this series of embedded networks (synaptic systems) “develops because there is something to communicate.” In sum, knowledge is both product and initiator of this sequence of events that result in what neurobiology calls learning. When used as a lens with which to examine MOOCs as a space for learning and sharing knowledge, it seems intuitive to utilize a neuronal network as a fitting and productive metaphor with which to explore this Object of Study (OoS) as not only an environment of constructed connections (from Learning Platforms like Blackboard to blog spaces for assigned student writing to student-created back channels in Facebook for student-directed discussions) but as a representation of cognitive transfer – how humans learn. In neurobiology terms, knowledge is both a material to be transferred between neurons but also an initiator that signals neuronal development, altering existing circuits and driving the creation of new neurons to make new connections (“Neurobiology”).

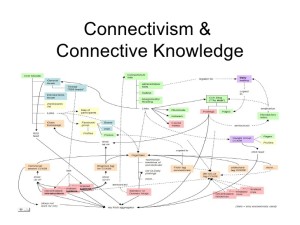

Stephen Downes refers to George Siemens’ definition of connectivism as “the thesis that knowledge is distributed across a network of connections, and therefore that learning consists of the ability to construct and traverse those networks” (Slide 15, Slideshare). Their MOOC, which he describes in a Slideshare presentation from 2009, explores the underlying learning theories informing the structure of the MOOC itself in light of their attention to how students best learn. While his course is not specific to freshman composition content, his theorizing of learning taking place within a network. Each component creates the “mechanisms to input, process and distribute content” (slide 27) – the course map or neuronal network — but students themselves “add to the map” (slides 46-56). The growth of this system — what student writers add and how they add it — might be discussed in terms of our neurobiology metaphor if we align Downes’ “mechanisms” with neurobiology’s initiating force of knowledge to be transmitted, addressing the questions, “how do we know?” and “what is knowledge?” Downes’ use of neurophysiology terminology illuminates a potential connection (what Foucault might say is a case of “minding the gap”) to the type of community networks typical of effective MOOC designs as “a ‘community of communities’” (Connectivism 120), a description which he illustrates using terminology drawn from the field of neuroscience. Downes’ description of a community-as-network asserts that “nodes are highly connected in clusters” and these clusters are defined “as a set of nodes with multiple mutual connections” which are instrumental in the movement or transmission of a “message from one community to the next” (Connectivism 120).

The parallelism to neurobiology is clear here: nodes, transmission, clusters, etc. However, for English Studies and Composition Studies in particular, while such a cellular-based network may ground this physiological process as a scientific set of facts, it does not address the broader question of how this translates to behaviors situated in dispersed cultural and social network systems. This is where Spinuzzi may fill the gap. For example, when Cormier writes of “knowledge networks,” it creates a point of intersection with Spinuzzi ‘s Activity Theory. Spinuzzi employs Hutchins’ theory of distributed cognition to illustrate how humans – not just freshman writers – learn most efficiently when in a collective and collaborative network of others.

Spinuzzi’s effort to correlate Activity Theory with Actor Network Theory provides a view of knowledge and learning from the perspective of activities performed in order to acquire or transmit knowledge. Spinuzzi distinguishes two competing discourse communities and their approaches to knowledge: designers and users, each creating very different hierarchies and relations to the other nodes within the network. His concept of centripetal and centrifugal “impulses” (20) creates a fascinating analogy with which to consider the discourse practices of these two communities and how that creates a perspective of knowledge or learning that could be useful within this FrankenTheory. His suggestion that the centripetal nature of a designer describes a discourse community that gravitates toward “formalization, normalization, regularity, convention, stability, and stasis” (20) may help us characterize a sort of knowledge creation privileging to which Foucault points in his work. The centrifugal nature of the user, on the other hand, represents “resistance…, innovation, — and chaos” (20), features that may also contribute to discussions of agency. This passage alone opens numerous connection nodes of analysis regarding the ways we envision networks functioning or moving knowledge. Spinuzzi’s identification of competing concepts of creation and operationalization of knowledge thus provides a useful tether to which the other theories may connect when examining this Object of Study.

Foucault argues that we must explore discourse “through the use of spatial, strategic metaphors” (emphasis mine) if we hope to perceive “the points at which discourses are transformed” (qtd. in Binkley and Smith). Not only are these points of transformation of a practical matter in the case of MOOCs (e.g., making choices between online platforms and applications to locate collaborative writing), they become the very “gaps” or “traces” (7) so key to Foucault’s theory of knowledge, revealing as they do points of contention and discontinuity where additional theorizing might take the discourse in new directions.

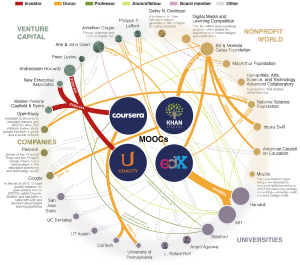

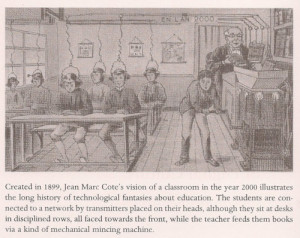

Foucault’s Archaeology of Knowledge offers this work a theoretical foundation with which to explore several key terms: knowledge and knowing (writing and learning), networks, disruptions of unities, différence and traces (169). With regard to knowledge in particular, Foucault argues that the reason some maintain that “the history of thought could remain the locus of uninterrupted continuities” creates a shelter “[f]or the sovereignty of consciousness” (12). Further, he argues that we must “question those ready-made syntheses” that inform current theories of the individual and society. For this FrankenTheorizing of MOOCs, this concept may provide a way to highlight the presence of a “status quo” element to current critical frameworks of knowledge and/or learning that are applied to scholarly treatment of MOOCs in Composition. Gardner and Cormier both point to ways the original MOOC design was more true to composition theory pedagogies of collaborative, decentered learning spaces. However, when MOOC spaces were corporatized through “Coursera, edX, and Udacity,” classes offered through MOOCs became prone to the “sage-on-stage teaching models” against which our field of composition has come to resist (Gardner). The “status quo” of decentering classrooms, however, always already exists within the larger “status quo” of an educational system that relies on assessment to measure what it deems “academic knowledge.” Within that system, MOOC designs are often perceived as “payload delivery systems,” making the online instructor complicit in this framing of teaching as a “content delivery expert” (Gardner).

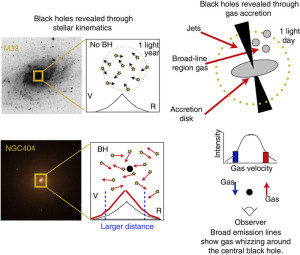

Foucault calls us to pay attention – much like Cynthia Selfe does – to ways in which points of disruption or tension in this discussion may actually define what we see. Foucault’s description on page 29 of how looking at absences or gaps (disruptions and displacements, the difference) actually helps define what we see makes its way into this FrankenTheory much the way black holes reveal the unseen by observing the actions of other bodies within its sphere of influence. Foucault writes, “in analyzing discourses themselves,” we should look for “the emergence of a group of rules proper to discursive practice” in order to see them as “practices that systematically form the objects of which they speak” (49). Foucault’s interest here is in the “discursive formation,” and I would argue at its core is the concept of knowledge and knowledge networks. With regard to previous comments on “delivery systems” and knowledge, this “disruptive” or transformative power of a MOOC creates a troubling gap in terms of how knowledge is conceptualized as content to be delivered, shared, and transferred within most academic communities. As a result, some Compositionists argue that our field must consider a refreshed pedagogy for learning spaces like MOOCs (Debbie Morrison’s “A Tale of Two MOOCs”). The assertion is that the traditional f2f methods and technologies cannot be simply overlaid onto the MOOC space with any hope of success.

Finally, theories of Ecology as advanced by Bateson and Gibson deal with knowledge in terms of more philosophical ideas rather than concrete transfers of material knowledge made within and between ecosystems. Bateson concerns himself with affordances and perspective within what he refers to as an ecology of the mind. Using a blind man and stick analogy to explore the “mental system” that is involved with knowledge and learning, “the stick” or the non-human node within the system that is considered an affordance serves as “a pathway along which transforms [or the effects] of difference are being transmitted” (465). For Bateson, then, the focal point of any discussion is not the “what” but the “how.” Gibson also focuses on the role of affordances – the environment – but in terms of knowledge, there is a considerable degree of unawareness that takes place between actor and activity. Perception is key. The human-centeredness may seem to situate the power of knowledge squarely in “the eye of the beholder,” but Gibson’s explanation of the role of other players in the environment (water, soil, animals) also suggests that the privileging of humans in the knowledge network may be tenuous.

Perhaps the most relevant “gap” in the discussion of MOOCs where Gibson’s theory may be helpful is his exploration of objects versus affordances. Gibson asserts that in an ecology network, objects should not be defined by their “qualities,” but by their “affordances” (134). He is careful to make the importance of this distinction clear when he observes that “to perceive an affordance is not [the same as] to classify an object” (134). He explains that such a distinction “rescues us from the philosophical muddle of assuming fixed classes of objects, each defined by its common features and then given a name” (134). In the case of a Composition MOOC, this distinction becomes especially relevant when our inquiry turns to the nature of distributed activities and network nodes in terms of student identity within the MOOC. By simply employing classifications such as instructor or student, too often these terms become infused with traditional connotations of power and knowledge creation a la “one to many” (Hart-Davidson) being transferred within a hierarchy of primary to secondary, rather than a pattern which follows a more diffused set of relationships fostered by the sort of collaborative-centered design of a cMOOC (Cromier). Further, Gibson’s theory points out that “[t]he richest and most elaborate affordances of the environment” are not even non-human agents. In fact, they are “provided by other…people” whose “behavior affords behavior” (135).Bourelle et al. describe MOOCs in this way, with knowledge being created and transferred (learning) as much between students as between student to instructor. The disruption created by the affordances of the networked and massive space itself thereby resists a fixed nature of objects. So, what does this mean for this OoS?

Knowledge is closely aligned with the concept of meaning. In Composition theory, this pairing is typically framed within key rhetorical concepts of audience and rhetor (writer). Gibson asserts that his theory of affordances provides “a new definition of what values and meaning are,” particularly in terms of how these affordances are directed. Gibson’s theory insists that (unlike neuronal pathways), an “affordance…points two ways, to the environment and to the observer” (140-41). Within the network of a Composition MOOC, such principles of meaning and knowledge allow the discourse to shift to the gap which commonly houses a “chicken or the egg” dilemma: is the MOOC environment to be seen as machine interface housing the human interface (the student-student or student-teacher connections), or are the human connections and interfaces transforming the physical network structure itself?

In short, when it comes to a Composition MOOC, what does it mean “to know” – for both teacher and student? These theorists take the discussion out of the realm of assessment, assignments, and the writing process, and shifts us into the realm of how we learnin a complex system of networked relationships. I deliberately do not refer to “networked space” as these four theories facilitate a move away from the structural configurations of boundaries, tools, and computer-mediated access, and into the realm of social networks.

Baseline Concept: The Locus or Framework of Learning

Of all these lenses, some are more useful than others when it comes to interrogating the MOOC space as a learning and teaching space. Gibson argues that “a place is not an object with definite boundaries” but is instead more of “a region” (136). Bateson famously observes that “the map is not the territory” (455). What do these mean for a new network theory meant to analyze a Composition MOOC? It is Bateson’s map/territory equation that may be most productive initially, as we endeavor to discuss a MOOC as uniquely networked on a level that must be theorized differently than a physical Composition classroom space filled with desks, one teacher, 20 students, textbooks (or even eBooks). When attempting to theorize a space as massive and open as a MOOC, it soon becomes clear that we cannot talk about its practices or its situatedness using the same framework and terms we use to analyze a traditional Composition course following traditional paradigms of f2f classroom theory. In fact, Bateson’s theory is predicated on the assumption that we must “change our whole way of thinking about mental and communicational process” (458). When Bateson notes that the “differences are the things that get onto a map” (457), it is a phrase remarkably reminiscent of Foucault’s differences, disruptions, and traces as the more productive locus of our attention when it comes to theorizing knowledge and networks within MOOCs. But just what does this mean – “the map is not the territory” – for MOOCs?

Of all these lenses, some are more useful than others when it comes to interrogating the MOOC space as a learning and teaching space. Gibson argues that “a place is not an object with definite boundaries” but is instead more of “a region” (136). Bateson famously observes that “the map is not the territory” (455). What do these mean for a new network theory meant to analyze a Composition MOOC? It is Bateson’s map/territory equation that may be most productive initially, as we endeavor to discuss a MOOC as uniquely networked on a level that must be theorized differently than a physical Composition classroom space filled with desks, one teacher, 20 students, textbooks (or even eBooks). When attempting to theorize a space as massive and open as a MOOC, it soon becomes clear that we cannot talk about its practices or its situatedness using the same framework and terms we use to analyze a traditional Composition course following traditional paradigms of f2f classroom theory. In fact, Bateson’s theory is predicated on the assumption that we must “change our whole way of thinking about mental and communicational process” (458). When Bateson notes that the “differences are the things that get onto a map” (457), it is a phrase remarkably reminiscent of Foucault’s differences, disruptions, and traces as the more productive locus of our attention when it comes to theorizing knowledge and networks within MOOCs. But just what does this mean – “the map is not the territory” – for MOOCs?

Neurobiology may help address this if seen as a metaphor for the type of learning that happens in a MOOC. MOOCs have been cast by many skeptics (including many composition scholars) as a troubling “break” from traditional models of higher education. However, if seen through the prism of learning models, a Composition MOOC space may instead become one that facilitates creativity and independent thinking by participants who become co-creative powers within a network of learners. The concepts of neurobiology applied as both metaphor and learning theory may facilitate this view.

Hart-Davidson’s article recently published in Invasion of the MOOCs: The Promise and Perils of Massive Open Online Coursesfocuses on student learning – specifically learning to write — in digital environments. He observes that digital technology like MOOCs may promote “peerlearning,” which he asserts is “the way most humans actually learn to write” (212). His analysis relies heavily upon Lev Vygotsky’s theory of learning, and especially the “zone of proximal development” principle, or ZPD (212-213). Briefly, we might summarize this theory in terms of a composition classroom learning model as “I do – We do – You do”: the instructor provides the learner with a scaffolded structure of activity that is at first mediated through modeling, then co-created or co-supported with student involvement, until finally the student requires no further mediated support and proceeds independently. Hart-Davidson summarizes Vygotsky’s importance to his approach to writing in MOOC classrooms by pointing out that peer learning involves “networks” – each individual bringing to the mix “a rich set of resources” that “boosts the learning potential” (213). The “zone of proximal development” or “ZPD” allows students to perform (i.e., write) and learn “better than one of us alone because we are surrounded by resources – one another – to scaffold our learning” (214). In such a network, “[t]here may be no stable individual ‘experts’ at any given moment, but among the group there exists a collective ability for a successful performance” (214).

She asserts that one course failed because of its reliance on a pedagogy that had not adapted its methods to the characteristics that define the web space as a learning space. In particular, she argues that the failed course did so due to its reliance on a “learning model that most of higher education institutions follow – instructors direct the learning, learning is linear and constructed through prescribed course content featuring the instructor,” a method not unlike the way many face-to-face (f2f) Composition courses are conducted. Such methods, she argues, are unsuited for the ways in which the Web “as a platform for open, online, and even massive learning creates a different context for learning – one that requires different pedagogical methods.” Morrison’s observation may illustrate one of the limitations of the neurobiology thread because the metaphoric image of a neural network isolates the picture somewhat, “tuning out” the environmental influences surrounding the neural pathways. In other words, the neural network nodes are a very small part of a much larger system, equated only to the “basic cellular mechanism in the brain” (“Neurobiology”). The dilemma for this application is whether this “smallness” can correlate to the “bigness” and complexity of a MOOC. This gap may be usefully bridged by integrating Spinuzzi’s work with chained activity networks and the concept of “connectivism” as applied learning theory.

Spinuzzi defines Activity Theory (AT) as “a theory of distributed cognition” that “focuses on issues of labor, learning, and concept formation” (62). Further, this theory continues to evolve, moving “from the study of individuals and focused activities to the study of interrelated sets of activities” (62) – networks that may include collaborative learning and development, both of which play significant roles in Composition pedagogy and MOOC structural designs. Such concepts and terms create a framework with which to explore how using a network lens provides a means with which to locate this discussion in terms of borders. As Morrison observes, such concepts and terms create a framework with which to explore how using a network lens provides a means with which to locate this discussion in terms of borders. As Morrison observes, the nature of a MOOC space does not easily align with the nature of an f2f classroom space. While the basic principles of Composition pedagogical theory must ground both in terms of the aforementioned priorities of student learning (as outlined by the NCTE in “Beliefs About the Teaching of Writing”), the nature of the space – the networks that represent the physical, the theoretical, and what AT calls the “dialectical” qualities of that space – create tensions at those boundaries which represent how to implement that learning. Morrison refers to the importance of “connectivism” as a corollary to “social constructivism,” a thread woven into modern pedagogical theory (and connected to principles of Ecology as well as Neurobiology) that states “students learn more effectively” when they are actively involved in knowledge construction that includes their own knowledge bases.

Activity Theory as distributed cognition incorporates mediation as a key concept. Described by Spinuzzi as “tools, rules, and divisions of labor” (71), mediators are used by individuals within an activity system to “transform a particular object with a particular outcome in mind” in a way that is meaningful and connected to a (discourse) community (71-72). Composition MOOCs as networks are often seen through the filter of traditional f2f structural limitations, leading to concerns such as those described by Halasek et al., who assert that reflecting on “the MOOC learning environment” reveals the “ways we understood – and sometimes failed to understand – our roles as teachers of composition and our students’ roles as writers and learners” (156). Again, the example of the Discussion Boards serves as an example of how Activity Theory allows us to productively analyze the MOOC environment. Halasek et al. observe that Discussion Forums are typically conceptualized as nodes in which student participants depend on the “controlled exhanges…shaped and guided by teachers…and oriented toward assignment expectations” (159). In effect, these learning nodes are mediated in specific ways by a limited number of people who occupy academically hierarchical positions with relation to the student-to-teacher activity pathways. In the revised iteration of their MOOC class, Halasek et al. discovered that students “actively occupied” these learning spaces and mediated the activity as well as the flow of content when they “engaged and even tested the faculty team by making their needs explicit and articulating the problems the instructional context posed” (159). Such meta-participation is then makes students the mediators who transform the learning environment through their activity and co-creating of the space.

Finally, Activity Theory involves “chained activity systems,” a concept that may account for the sort of “organizational…boundaries” that create “informal linkages” between activities that could be interpreted as metacognitive nodes where transfer takes place (Spinuzzi “Networks” 74-77). As Spinuzzi explains, there are two types of work that takes place in systems: modular and net work (“How”). Complex tasks in Modular work is described as more compartmentalized and specialized, with clear boundaries and hierarchical orders of authority. Net work refers to the “coordinated work that holds” complex systems together (“How”). Foucault’s concepts of disruption and chaos as areas of transformation may fit here as Spinuzzi explains that modular work (a system of activity that emerged from the Industrial Revolution) has been “disrupted” or “destabilized” by technology’s impact. As a result, homogenous units of work gave way to “heterogenous networks…[that] form dense interconnections among people, texts, tools, etc.” (“How”).

Spinuzzi applies Activity Theory in terms of connected activity systems in which mediators – which in this case may be the digital space itself, the technology, or the pedagogical system that functions as a genre – provide the “tools, rules, and division of labor” (71) to create a system suited for “distributed cognition” (69). In terms of MOOCs, Spinuzzi’s characterization of “contradictions” as “engines of change” and transformation (a key component of Activity Theory) becomes a means of considering the impact of designers’ pedagogies as well as the agency afforded users in this learning space.

Further, Spinuzzi asserts that chained activities “don’t chain so much as they overlap and interfere with each other,” allowing the participants “to take on many functions” (“How”). This distinction is reminiscent of Syverson’s application of ecology to the Composition classroom in terms of how it allows us to treat a MOOC space as a “complex system” rather than a technology-mediated space. As a result of these theoretical combinations, discussions of the most productive teaching/learning models for a MOOC allow more credence to the “many-to-many” as opposed to one of “one-to-many” (Hart-Davidson).

For Composition, metacognitive transfer has become an increasingly foregrounded concept in discussions of student writing. For the Composition MOOC, AT becomes especially productive as a way to analyze it as a potentially viable mediator of student writing. It also offers a point of alignment with the neuronal metaphor (the way axons and dendrites constitute independent nodes of activity as part of the larger neuronal system that make up brain activity) as well as ecology theories.

But what of Agency within these complex systems? What of the students’ ability to co-create their learning and knowledge?

Baseline Concept: Agency

Foucault describes members of a discourse community as existing inside “a web of which they are not the Masters, of which they cannot see the whole, and of whose breadth they have a very inadequate idea” (126). These notions of control and scope are key to understanding and exploring the notion of agency in MOOC spaces, in particular how that impacts writing pedagogy. Because Foucault’s theories challenge the linear homogeneity of not only academic discourse but knowledge conventions as well, the notion of hierarchical agency as a power dichotomy comes under scrutiny.

As stated earlier, classrooms are often analyzed in terms of structural components: the mechanical, the hardware, the situatedness of student and teacher. In the case of any online classroom including MOOCs, it is easy to believe there is an individual mastery over the network, which Spinuzzi might refer to in terms of designer, as when the architects of that network exert an unseen filter in the form of a control system. Agency, then, within such networks must also be a point of analysis, and is a boundary where all four theories contribute to one degree or another.

Foucault’s Definition of Agency – Foucault resists essentialisms and absolutes. Therefore, his approach to agency is one that resists what he refers to as a “history of ideas” that promotes a linear approach to influences — a one-to-one, top-down hierarchy. Instead, he seems to locate that agency in moments of disruption and discontinuity, which networks facilitate in their “redistributions” (5). He argues that the “sovereignty of the subject” (12) is problematic, one fostered by the history of ideas. His assertion, through his archeology of knowledge, is to dethrone or decenter the subject. If we view “subject” as having the sort of primary agency as might a designer (Spinuzzi), a theory that decenters that subject’s hierarchical (and linear) primacy would fit a networked system in which agency is diffused. The MOOC’s essential networked structure can serve Foucault’s argument, but only if the hierarchical system of one teacher distributing knowledge to many students is disrupted. Some MOOCs, as Hart-Davidson points out, fail to operate in this way, but there are cases, such as the online classrooms cited by Bourelle et al. as well as Halasek et al., which operationalize a networked, student-prioritized course that diffuses the agencies of knowledge generation and transfer to tutors as well as students. Moreover, a consideration of how their online course failed to produce envisioned learning outcomes – a gap – served to focus their theorizing efforts to address these disruptions via a redistribution of agency. Foucault’s theory both frames the disruptive powers of networks as well as serving to illuminate the gaps where questions of agency may be asked.

Spunuzzi and Agency: Vygotsky’s theory of learning might locate agency in the relationship b/w nodes — teacher, student – which may be discussed in terms of scaffolding. The scaffolding, of course, takes on an entirely new location in a MOOC, but activity theory may allow this to be applied in a more decentered way than Vygotsky originally intended when he wrote about educational strategies for teaching children new concepts. While Vygotsky’s theories have been folded into Writing Center and even Composition theories, at their core is a collaborative activity. All too often, however, that collaboration still relies on a designer (tutor / teacher) who crafts the structure for that scaffolded behavior. In the case of MOOCs, the course design begins within the institutionalized origin of the course, but the networked system may allow designer agency to be diffused through the course through peerlearning nodes, some predesigned and others initiated and created by students (as in the composition MOOCs of Hart-Davidson and Bourelle et al.). As Downes observes, when MOOCs are designed following theories of Connectivism, students are empowered (i.e., are afforded agency) by the space itself to become “creators of learning” (Downes “Connectivism”). Teachers as well adopt “new roles” as “coaches and mentors” (Downes “Connectivism”). Due to this increased and diffused agency, learning then becomes “a network phenomenon” (Downes). Spinuzzi’s use of distributed cognition (Activity Theory) and interconnections also maps onto MOOC spaces in potentially useful ways, particularly when focusing on “interrelated sets of activities” (62) rather than the individual learner.

Ecology and Agency: For Bateson, meaning is “projected” onto the world by the perceptions and subjectivity of the viewer. Dividing potential agents into “creatura” and “pleroma,” he sets up a binary of subject/object. To set up the question, “what does it mean to know,” Bateson’s agency is diffused, but not shared. It is still very much a human-centered approach to networks, knowledge, and agency, an approach which Spinuzzi might find appealing. Gibson’s theory pushes back against the worldview born of the Enlightenment that sees the world in terms of mechanical cause and effect. Affordances are potential activity that allow agency, but have no agency of their own per se. The environment is not a “cause” of action, but instead facilitates it. The interactivity of an environment’s connectivity is one of give and take, self-regulating. Non-human actors (animals) are not simply machine-like, responding to environmental stimuli. His concept of agency is a theoretical one meant to disrupt a subject-object / subjective-objective dichotomy. Most interestingly, “[a]n affordance points both ways, to the environment and to the observer” (129). This relationship or network, while still privileging the human actor, opens up a means of exploring the structural elements of a created structural network (a system of connections that afford students and instructors to create relationships one with the other) of a MOOC. Affordances themselves, therefore, seem to possess agency of a kind. Their existence does NOT depend on their perception. Actions, then, reveal how animals are using those affordances, which Foucault might see as a trace or gap that results in new possibilities for analysis (statements).

Neurobiology and Agency: The neurotransmitters are the key to connectivity within the network, and specifically between synapses. Neurotransmitters are the key to movement within a neural pathway. A chemically-based reaction to stimuli, these “energy impulses” create a connection between two neurons. The very act of transmission transforms both neurons, opening “channels” and allowing movement through the phenomenon not unlike a differential seeking balance (“Neurobiology”). This action may be useful to discuss as a metaphor of how the types of peer writing practices employed in a MOOC writing class transmit and encounter text; emphasizing the rhetorical importance of audience by introducing the authority of “reader” may change or alter the writer’s perception of what he or she is doing and can have profound effects on a student’s understanding of the process and the text. (Lisa Ede and Andrea Lunsford wrote about this topic decades ago and more recently in a compilation that explores the current trend in English Studies to better foreground audience in Composition.) The usefulness of this metaphor is wide ranging, as the neurotransmitter’s role as agent or node can be applied to questions of student agency as well as affordances of the system itself (that is, technology choices made by both the course designers as well as the students to facilitate learning and/or writing).

Summation: Syverson offers a justification for an ecological approach to Composition, one which translates over to this OoS as well. As she observes, the layering of theory is “crucial in developing new knowledge” (Syverson 2). As well, we might argue that, just as MOOCs should be seen and theorized as a complex system, these theories are part of that system. In the end, as a unifying element of this FrankenTheory, Ecology seems the most productive of the four in terms of framing discussions of MOOCs as spaces for teaching, learning, and practicing writing. Too often, MOOCs seem to be cast in terms of a “simple system” of teacher-student relationships, when in reality – and as Foucault, Spinuzzi, Neurobiology, Bateson, and Gibson all demonstrate – it is far more complicated than criticisms based on “mechanistic explanations” permit (Syverson 2).

Indeed, as Syverson posits, the cMOOC is a “meta-complex system,” one wherein Ecology Theory may productively integrate (subsume) Neurobiology, Activity Theory, even Foucault. As Syverson argues, such ecologies allow us to discuss “writers, readers, and texts” as part of a complex system that is composed of “self-organizing, adaptive, and dynamic interactions” (3). This system, as she envisions it, is built of “interrelated and interdependent complex systems and their environmental structures,” structures that include “theoretical frames, academic disciplines, and language itself” (3) along with – I argue — assumptions about knowledge and agency.

In Music, It’s Called A Deceptive Cadence: I must admit, I’ve been suspicious of MOOCs as a productive place for freshman writing instruction since I first learned of them a few years ago. As a proponent of our field’s insistence upon smaller-scaled classrooms following a student-centered workshop / studio activity design, the sheer size and decentered nature of the MOOC seemed destined for trouble. I have taught freshman writing sequences online in the past, and it quickly became clear to me that the nature of the space cannot simply mirror that of the f2f classroom. The MOOC design takes this distinction to entirely new levels of complication.

But the very nature of our field demands flexibility and openness to new ground and new theories with which to best equip college-level writers for the demands of communication across disciplines and across technology-mediated spaces. MOOCs may be in their early stages of a full life in the realm of Composition Studies, or they may be on the road to extinction – a fast-burning flame. Another possibility is that they must simply be reclassified, recognized as a unique learning space for unique student populations. What the scholarly discussions seem to reveal is that we as a field are not yet certain how to deal with MOOCs, all the more reason why such theorizing (even after the fact) can be so productive.

Coda: If our field approaches the Composition MOOC as an ecology, how might the conversation change? How will it reflect the “enunciative function” identified by Foucault (88)? What new threads, nodes, or means of transmission might emerge as part of the discourse if we apply theories of learning like Vygotsky through the lenses of Neurobiology and Activity Theories combined? How might the goals and motives of our pedagogy evolve if we treat the technology of MOOCs as having productive, rather than reductive, agency in the ways students learn to write in a massive digitally-mediated space?

When these digital spaces are built as adaptive, complex systems rather than static delivery systems based on one-to-many models like Coursera and eduX courses (Hart-Davidson), how will the conversation be transformed?

Questions aside, as important is how we as a field of study will frame this discussion of the MOOCs place in 21st century higher education. Syverson’s question seems productive to our response: “Can the concepts currently emerging in diverse fields on the nature of complex systems provide us with a new understanding of composing as an ecological system?” (5). Her question posits the very behavior itself – composing – as a system (Spinuzzi might call it a networked activity) itself, not a learned behavior designed to produce a product. The transformation of our field of view afforded by this proposed FrankenTheory may allow those of us in the field of Composition Studies to bring this question, and these three key areas of theoretical overlap, to the forefront of this discussion in an effort to move us forward.

Works Cited:

Barlow, Aaron. “Teachers and Students: Machines and Their Products?”Academe Magazine 26 May 2013. Web. 1 May 2014.

Bateson, Gregory. Steps To An Ecology of Mind. New Jersey: Jason Aronson Inc., 1987.

Binkley, Roberta and Marissa Smith. “Re-Composing Space: Composition’s Rhetorical Geography.” Composition Forum 15 (2006). Web. 1 Mar. 2014.

Bourelle, Tiffany, Sherry Rankins-Robertson, Andrew Bourelle, and Duane Roen. “Assessing Learning in Redesigned Online First-Year Composition Courses.” Digital Writing Assessment and Evaluation. Eds. Heidi A. McKee and Danielle Nicole DeVoss. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press, 2013. Web. 2 Feb. 2014.

Cormier, David. “Knowledge In A MOOC.” YouTube. 1 Dec. 2010. Web. 1 Feb. 2014.

Downes, Stephen. Connectivism and Connective Knowledge: Essays on Meaning and Learning Networks. 19 May 2012. Creative Commons. Web. 30 Mar. 2014.

Downes, Stephen. “The Connectivism and Connective Knowledge Course.” Slide Share. 24 Feb. 2009. Web. 30 Mar. 2014. < http://www.slideshare.net/Downes/the-connectivism-and-connective-knowledge-course>

Downes, Stephen and George Siemens. “Connectivism and Connective Knowledge: Getting Started.” MOOC course, University of Manitoba. 2009. Web. 30 Mar. 2014. <http://elearnspace.org/media/GettingStarted/player.html>

Foucault, Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge and the Discourse on Language. New York: Vintage Books, 1972. Print.

Friend, Chris. “Will MOOCs Work For Writing?” Hybrid Pedagogy: A Digital Journal of Learning, Teaching, and Technology. 28 March 2013. Web.

Gardner, Traci. “The Misunderstood MOOC.” Bits: Ideas for Teaching Composition. Bedford / St. Martins. 5 June 2013. Web. 1 May 2014.

Gibson, J. J. “The Theory of Affordances.” In R. E. Shaw & J. Bransford (Eds.), Perceiving, Acting, and Knowing. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1977. pp. 127-143.

Hart-Davidson, Bill. “Learning Many-to-Many: The Best Case for Writing in Digital Environments.” Invasion of the MOOCs: The Promise and Perils of Massive Open Online Courses. Eds. Steven D. Krause and Charles Lowe. Anderson, SC: Parlor Press, 2014.

Mitrano, Tracy. “MOOCs as a Lightning Rod.” Inside Higher Education 31 May 2013. Web. 1 May 2014.

“Neurobiology.” Rediscovering Biology. Annenberg Foundation, 2013. Web. 31 Mar. 2014.

Norman, Don. “Affordances and Design.” jnd.org. 2004. Web. 18 Mar. 2014.

Spinuzzi, Clay. “How Are Networks Theorized?” Network: Theorizing Knowledge Work in Telecommunications. NY: Cambridge UP, 2008. 62-95.

Spinuzzi, Clay. Tracing Genres through Organizations. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003.

Syverson, Margaret A. “Introduction.” The Wealth of Reality: An Ecology of Composition. Southern Illinois UP, 1999. 1-27.

“What You Need to Know About MOOCs.” The Chronicle of Higher Education: Technology. 1 May 2014. Web. 1 May 2014.