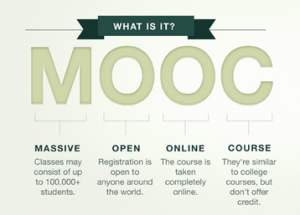

The rhetorical nature of classroom spaces has certainly influenced our field’s scholarship when exploring digitally mediated writing classrooms. Terms such as constructed, architecture, location, ecology, environment, and space appear regularly in our field’s discussions of where and how writing takes place in FYC (first-year composition), typically in terms of ways location influences and mediates student identity and pedagogical practices. However, spatiality also provides other useful layers of analysis when exploring the composition classroom and our field’s discourse. Michel Foucault argues that we must explore discourse “through the use of spatial, strategic metaphors” (emphasis mine) if we hope to perceive “the points at which discourses are transformed” (qtd. In Binkley and Smith). While Foucault was concerned with “relations of power,” this Case Study is designed to suggest that our exploration of composition classroom spaces need not be limited to the geometric, architectural renderings of four walls, tables, and chairs, or – for that matter – a computer terminal, a Blackboard platform, and an Internet connection. In the last two case studies, I have examined MOOCs from a structural lens (how it works) as well as a pedagogical lens (how we teach). For this case study, it may be productive to “drill down a level” and use a different architectural metaphor to theorize MOOCs, this time using a lens that foregrounds the learning process (how students learn) itself. Given the subject of MOOCs as a space for learning and sharing knowledge, it seems intuitive to utilize a neuronal network as a fitting and productive metaphor with which to explore this Object of Study (OoS) as not only an environment of constructed connections but as a representation of cognition – how humans learn.

A Brief Literature Review / Overview

Three scholars provide the foundation of this Case Study, all of whom approach the subject of learning and composition studies for somewhat different purposes. However, their points – or nodes – of intersection provide an interesting network of terminology and theory with which to inform my approach to this OoS. Margaret Syverson takes an ecological systems’ approach to the subject of the composition classroom, while Bill Hart-Davidson’s article is more narrowly concerned with MOOCs and learning theory. The final component of this Case Study is one of the early designers of MOOC-based college learning, Stephen Downes, who builds upon George Siemens’ theory of Connectivism (an outgrowth of Vygotsky’s theories of learning and Hutchins’ theory of Distributed Cognition) in his work in MOOC design and deployment.

Syverson begins her book on An Ecology of Composition with the premise that a student’s “process of composing” – i.e., learning – takes place within a dynamic “complex system,” which she theorizes using ecological principles (2-3). Writers interact with and are affected by this environment, as they learn through a variety of (mediated) encounters: instructor-student, student-student, readers-writers, etc. She explains such interactivity is a “network of independent agents – people, atoms, neurons” which “act and interact in parallel with each other, simultaneously reacting to and co-constructing their own environment” (3). Her theory is an interdisciplinary one, borrowing from the fields of biology, ecology, behavioral sciences, and learning theory in order to address what she perceives as gaps in our field’s ability to account for student writer improvement (or lack of same) (2). She argues that our discipline often focuses primarily on the “social; there is little discussion of the material or physical world as a significant component of composing activity” (24). If we approach this idea of composition as an ecological system, one which narrows the lens to the realm of learning, then a neuronal metaphor may offer new language and frameworks with which to consider the MOOC as a space for composition.

Stephen Downes refers to George Siemens’ definition of connectivism as “the thesis that knowledge is distributed across a network of connections, and therefore that learning consists of the ability to construct and traverse those networks” (Slide 15, Slideshare). Their MOOC, which he describes in a Slideshare presentation from 2009, explores the underlying learning theories informing the structure of the MOOC itself in light of their attention to how students best learn. While his course is not specific to freshman composition content, his theorizing of learning taking place within a network – complete with discussions of how distribution nodes like Moodle (slide 20) Twitter (slide 24) and UStream (slide 25). Each of these components creates the “mechanisms to input, process and distribute content” (slide 27) – the course map — but students themselves “add to the map” (slides 46-56). Both Downes and Siemens’ work on MOOCs provides the “ideal” baseline for my approach to composition MOOCs.

The key contributor/node of operationalization for this third Case Study is Hart-Davidson’s article recently published in Invasion of the MOOCs: The Promise and Perils of Massive Open Online Courses, which focuses on student learning – specifically learning to write — in digital environments. He observes that digital technology like MOOCs may promote “peerlearning,” which he asserts is “the way most humans actually learn to write” (212). His analysis relies heavily upon Lev Vygotsky’s theory of learning, and especially the “zone of proximal development” principle, or ZPD (212-213). Briefly, we might summarize this theory in terms of a composition classroom learning model as “I do – We do – You do”: the instructor provides the learner with a scaffolded structure of activity that is at first mediated through modeling, then co-created or co-supported with student involvement, until finally the student requires no further mediated support and proceeds independently. Hart-Davidson summarizes Vygotsky’s importance to his approach to writing in MOOC classrooms by pointing out that peer learning involves “networks” – each individual bringing to the mix “a rich set of resources” that “boosts the learning potential” (213). The “zone of proximal development” or “ZPD” allows students to perform (i.e., write) and learn “better than one of us alone because we are surrounded by resources – one another – to scaffold our learning” (214). In such a network, “[t]here may be no stable individual ‘experts’ at any given moment, but among the group there exists a collective ability for a successful performance” (214).

Hart-Davidson’s contribution to this next layer of analysis is especially productive here, as he asserts that these peer networks and their resource potential lead to “the possibility of … near-constant connection with a peer network [as]…the best reason to think about digital technology in relation to writing, learning, and teaching” (215). Along these lines, he points out that MOOCs as a “model of learning” are far too often designed as a “learning one-to-many” model, which evidence suggests “work less well than peer learning in the zone of proximal development” (215). Thus, Hart-Davidson’s study of MOOCs as theorized using learning theory provides a sense of the framework in which this Case Study may fit.

Neurobiology as Metaphor: Conceptualizing Learning as a Knowledge Interactivity Network

While it should be acknowledged here that Downes resists the equation of the computer = human mind analogy as a myth, his reasoning behind that resistance offers a useful segue into the use of neuropathways as a more precise and productive metaphor. Downes writes that the equation of the way our brains work – through external stimuli, transfer of information through neurotransmission signals – at first glance may seem akin to the type of “processing” performed by computers, but he rightly argues that communication is much more than a simple transmission to be processed (Connectivism 122-123). Moreover, he points out that the originating metaphor of mind:computer originated prior to the technology itself (123), and as our understanding of the brain physiology has advanced, so too must the metaphor.

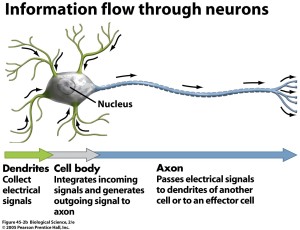

Borrowing heavily from the online textbook chapter, “Neurobiology,” as a guide to this metaphor, I would assert that the way students learn to write in any classroom follows the same highly generalized schema of the brain function described as “(1) take in sensory information, (2) process information between neurons, and (3) make outputs” (“Introduction”). However, such a model is obviously limited, and does not represent the complexity of learning and teaching that happens in composition classrooms – especially those that practice student-centered pedagogy models. Downes refers to the type of community networks typical of effective MOOC designs as “a ‘community of communities’” (Connectivism 120), a description which he illustrates using terminology drawn from the field of neuroscience. Downes’ description of a community-as-network asserts that “nodes are highly connected in clusters” and these clusters are defined “as a set of nodes with multiple mutual connections.” These connections are instrumental in the movement or transmission of a “sessage from one community to the next” (Connectivism 120). What makes Downes’ use of neurophysiology terminology so appropriate to this case study is the way in which he applies it to the MOOC. He clearly points to the less effective organizational schema of a classroom designed to move information unidirectionally in the “school-and-teacher model…which is a hub and spokes model” and favors the alternative “community of practice” mode which “maximizes the voice of each of its members” (121). His description of the theory of connectivism relies on terminology very similar in language and meaning to neurobiology, suggesting a useful correlation to the composition field is already in progress. For example, Cormier writes of “knowledge networks” and Spinuzzi (as well as other Activity Theorists) points to Hutchins’ theory of distributed cognition to illustrate how humans – not just freshman writers – learn most efficiently when in a collective and collaborative network of others.

Terminology

At this point, it would be useful to create a map of correspondence between key neurobiology terms and analysis of learning in Composition MOOCs. Neurobiology definitions are drawn from Chapter 10 of the online textbook Rediscovering Biology. As terms commonly create the creative connection potential between metaphor and object, these become the means of addressing the key network questions at the heart of the Case Study. The primary terms are defined here; others are defined in the course of addressing key questions of networks in the section that follows.

- NEURON: a “specialized cell” that “works by changes in its voltage.” It is dependent on, and sensitive to, changes in its environment in terms of ions. The chemical imbalances create movement across the membrane of the cell, leading to exchanges in material or electrical impulses (i.e., information).

- NETWORK: a vast series of neurons that make up the nervous system and brain.

- SURFACES or MEMBRANE: critical borders of a cell that facilitate transfers of energy, chemicals, and influence transmission or nerve impulses along “sodium channels.” Transmission along these channels is only one-way.

- AXON: the long extension at the opposing end of the neuron that “ends in ‘synaptic terminals’ which send signals to the dendrites of an adjacent neuron.”

- DENDRITE: small extensions at one end of the neuron designed to “receive information.”

- VOLTAGE–GATED CHANNELS: see neuron and membrane definition.

- EXOCYTOSIS: process in which neurotransmitters are released.

- SYNAPSE: the “meeting points” between neurons.

How It Works: Mapping the Terminology to Questions of Application

1. How does the metaphor define this OoS?

Neurobiology as metaphor provides a useful structure and vocabulary that in many ways parallels the MOOC as a student learning space. This parallelism seems well suited to facilitating an exploration of key concepts of neurobiology as a means of illuminating the connections between MOOC designs. Through this, I am hoping to discover new means through which to analyze how MOOCs may best maximize the benefits of networked learning and knowledge transfer as key features of a technology-mediated writing classroom space. A case study of this length cannot possibly fully develop such a plan, but it may provide the groundwork for a more intensive operationalization at another time. In short, this Cyborg-theory may lead to a fully realized Franken-theory for Composition MOOCs.

The neurological network system of neurons may be visualized as a network within a network, a scalable system w/in a system. While any writing classroom might borrow this metaphor overlay to explain the relationships between participants within the classroom, as well as the relationship between the classroom and the educational institution hosting it, the MOOC classroom model creates additional areas for analysis. While the previous two case studies examined other layering possibilities (the structural lens, followed by the pedagogical lens), a neurobiology metaphor allows for a more narrow scale of lens, allowing for a closer examination of what is at the heart of the classroom space: how we learn. The neurobiology metaphor provides a way of parsing that process as both a biological as well as a writing theory network of activity. The connection seems obvious, given our field’s emphasis on accommodating multiple learning styles in our lesson designs, as well as a call to be hyper-aware of technology’s mediating power and influence on pedagogy as well as learning, a vigilance called for by Cynthia Selfe in her 1999 book Technology and Literacy in the Twenty-First Century: The Importance of Paying Attention.

Despite this utility, this metaphor may not be as widely useful in terms of mapping all of the connective potentiality for learning as mediated through a Composition MOOC. What it does provide, however, is a useful redirection, moving the discussion out of the realm of socio-cultural theory and into a more pragmatic realm of asking, “How does this space and technology facilitate learning and transfer for our student writers?” The neuronal pathway activity that corresponds to learning and memory are part of that deeper layer, a layer that serves to reinforce attention to the student perspective.

2. Nodes & Agency: Relationships Defined & Transformed by Neurobiology (What and/or who is a network node & how are different types of nodes situated?)

An immediate assumption commonly ascribed to node identification within a networked classroom like a MOOC is that the human participants are the nodes. Another possible and logical application is that each mediating digital feature (such as those examples illustrated in Downes and Siemens MOOC) serves as a node, attracting and housing as they do participation, direction, and collaborative action. For example, students working in a Composition MOOC might be asked to participate in a collaborative space such as a Wiki to create a group research writing exploration project, creating a node of activity predetermined by the primary instructor. Such a node would simply be a creation of the instructor in terms of course design, but becomes a co-created space thanks to the ways student participants use it.

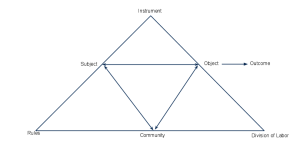

In Hart-Davidson’s article, he represents these learning communities through visualizations which, when compared to an image of a neural network, suggests possible overlap potential between the two systems.

Hart-Davidson reviews “the way learning involves interaction” (215), incorporating graphics which “represent…our thinking about what writing classrooms should look like” and “the kinds of interactions we think best facilitate learning to write” (216). He uses these representations to explore how, in the history of composition studies, we have “decentered” the traditional classroom model in a “disruption of the lecture model in favor of more engaged, peer-learning models in the undergraduate curriculum” (quoting Harris, 216). His “one-to-many” model (the center graphic above) is the lecture model (216), contrasted with the preferred “studio model” (above left) or the one-to-one system (above right) of “peer groups – few to few” (217). He locates the new MOOC model – see graphic below as a “many-to-many learning infrastructure” that may be the apex of online learning modes, one which he asserts “[m]ost…MOOCS…get wrong” (217).

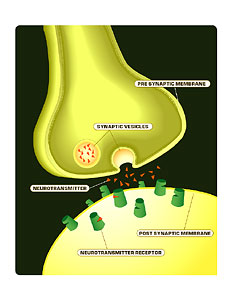

Just as a neural node – the neuron – serves as a locus or site of transmissions between neurotransmitters and neuroreceptors, it also serves as a facilitator of that transmission of signals (knowledge or information) via synapses, defined as the “meeting points” between neurons (Chapter 10). The synaptic space separating the two neurons is more than just a gap; these are “functional links between the two neurons” over which “signals are transferred” (Chapter 10). This transfer is facilitated by structural configurations, key to the system’s operation and what we might refer to as “knowledge building.” As mentioned earlier, the discourse of “space” is one that is a common site of tension discussions of pedagogy, access, technology, and digital spaces, and therefore may be reconceptualized using this metaphor.

The students, instructors, and teaching assistants operating in a Composition MOOC (such as the situation described by Halasek et al. in Case Study 2) might be described using these terms, as long as the classroom is designed according to the “Many-to-Many” model explored by Hart-Davidson. Yet an alternative representation may suggest that instead of seeing these nodes / neurons as the active agents in both the productivity as well as design and direction of the learning (via synaptic transmissions), they might be perceived as the larger framework itself, with nodes being located in the transmissions themselves. This alternative, however, is troublesome in terms of metaphoric alignment, and may be better expressed as networks of nodes embedded within networks of nodes – a complex system understood in terms that function equally well along a scale of size. In other words, individual neuronal nodes might be interpreted as sites of collaborative activity set up by the course designers as infrastructural lines of connectivity potential (like Downes’ examples of Twitter, the course Moodle Forums, or UStream). However, the metaphor also allows for a smaller scaled analysis, with each node / neuron representing the human actors in the system, learning through connectivity. This is the feature which aligns best with Syverson’s Ecology of Composition, and – more importantly – Hart-Davidson’s description of learning in a MOOC space.

Image of Neuron. The dendrites are in green; the axon is in blue. Taken from http://www.uic.edu/classes/bios/bios100/lectures/nervous.htm.

If we think of the brain as an incredibly complex system, one in which neural pathways are active and creating multiple connections and covering a wide range of spatial locations, it would be difficult to envision a successful MOOC as one in which a “learning one-to-many” model would produce the kind of learning and writing our field has come to accept as optimal. However, this is also one area where the metaphor may falter, as the synaptic transfer occurs in “only one direction” over synaptic space (Chapter 10). As our field actively resists returning to any practice premised upon a one-way power structure (i.e., transmission) between teacher and student as described in Freire’s banking model of education, this unidirectional transfer is troublesome. However, what if we think of this as a communications network, in which communication between speaker / rhetor / writer and listener / audience / peer reader (or instructor) requires that we see this in terms of delivery, not power? In this light, an understanding of presynaptic and postsynaptic neurons create a critical unity, perhaps even in terms of collaborative energy. The presynaptic neuron’s firing transmits information across the axon, a “long extension at one end of the neuron that “ends in ‘synaptic terminals’ which send signals to the dendrites of an adjacent neuron” called the postsynaptic neuron. These neurological elements may be rather easily translated into a discussion of peer-to-peer communications when student writers are framed as co-creaters of the learning taking place – made possible by the type of peer-to-peer activity promoted by Downes, Siemans, Syverson, and others who see the composition classroom as more of an ecology than a top-down delivery system.

This adjacency may be another area where this metaphor falters. The neurological system is predicated on physical proximity – a system of neurons transfer information based on physicality. Can a MOOC space adequately replicate this in a way that is as productive to learning as a face-to-face classroom space provides? This is a key challenge to Composition MOOCs. Proponents of MOOCs like Downes would argue that the digital technologies available to us as teachers allows for a level of interactivity not possible just years ago. Digital tools like Skype, Google Hangout, Group Prezi spaces, and even Facebook create potential for what we might refer to as synaptic plasticity, a feature of the human neural network that promotes change as a way of ensuring viability and learning (Unit 10). Creating new forms of synaptic spaces may be a feature of the more effective MOOC designs. These are interesting tensions that may prove productive to future analyses.

3. Agency and Relationships: Nodes, Neurons, Synapses

The neurobiology text reveals that there is no standardized neuron – they come in varying sizes, all of which must be employed in signal transmission and processing activity for the network to function efficiently. This physiological characteristic of the neural network may become important to discussions of how learning takes place in a MOOC when considering the dependence on a collaborative “many to many” model (Hart-Davidson). The premise of the composition MOOCs deemed “successful” (although no real assessment studies have been done to substantiate that) is that learning is decentralized; in other words, the massiveness of the MOOC space demands a model of classroom design and learning facilitation that employs peer-to-peer knowledge building. As Hart-Davidson observes, “digital technologies” have the potential “to get us closer to supporting the way most humans actually learn to write” (212). More specifically, he is pointing to “Peerlearning” (212), a term that stems from Vygotsky’s theory that employs “peer scaffolding” (213). In essence, this theory is based on the idea that “we learn most and most effectively from peers rather than adults or other figures” (213). Even though Vygotsky was writing about children, his theory has become an important thread in writing center theory as well as in composition. Further, if we apply the neurobiology metaphor, this becomes increasingly important to discussions of Composition MOOCs.

Neuroscientist Wolfhard Almers (“Expert Interview Transcripts”) indicates that the neuronal system is massive, making it a suitable metaphoric partner to this discussion of learning networks in MOOCs. Moreover, the size and activity of neurons in the brain are not uniform: “On average, [neurons] make about a thousand connections, very roughly. But there are neurons that that send a signal to only one other cell. And there are other neurons that get input from only, you know, maybe ten cells. So it varies quite enormously. There are big neurons and small neurons” (Almers, “Expert Interview Transcripts”). This may suggest that productive activity taking place within the network between cells (what we might call learning as knowledge transfer) isn’t dependent on one node (the teacher or tutor in the one-to-many or one-to-one model described by Hart-Davidson). In Composition theory, this valuation of the individual student contributions and voices is important to a student-centered classroom framework, one which accounts for varied learning styles in classroom design.

The neurotransmitters are the key to connectivity within the network, and specifically between synapses. Neurotransmitters are the key to movement within a neural pathway. A chemically-based reaction to stimuli, these “energy impulses” create a connection between two neurons. The very act of transmission transforms both neurons, opening “channels” and allowing movement through the phenomenon not unlike a differential seeking balance (Chapter 10). This action may be useful to discuss as a metaphor of how the types of peer writing practices employed in a MOOC writing class transmit and encounter text; emphasizing the rhetorical importance of audience by introducing the authority of “reader” may change or alter the writer’s perception of what he or she is doing and can have profound effects on a student’s understanding of the process and the text. (Lisa Ede and Andrea Lunsford wrote about this topic decades ago and more recently in a compilation that explores the current trend in English Studies to better foreground audience in Composition.) The usefulness of this metaphor is wide ranging, as the neurotransmitter’s role as agent or node can be applied to questions of student agency, affordances of the system itself (that is, technology choices made by both the course designers as well as the students to facilitate learning and/or writing).

4. What is moving within the network?

The neuronal system is akin to a cascade. One neuron does not work in isolation – it is a network of networks, embedded in an ecosystem that makes knowledge acquisition (and memory – which might be described in terms of “transfer potential”) possible. Similarly, in a decentered composition classroom, the importance of collaborative peer networks is key to learning and writing growth. The question has been raised by Syverson, however, is whether or not the way we teach writing promotes the type of long-term learning that is needed to translate into transfer. She suggests that there “is no evidence that students are writing, reading, or thinking better than any time in the past” (2). What, then, is happening – or more to the point, not happening – in the learning space of the composition classroom? This is where the neurobiology metaphor may provide fresh pathways to address this.

The term Long-Term Potentiation (LTP) describes a process crucial to learning and memory formation in which the synaptic communication is modified over time. Postsynaptic neurons’ firing rate “depends on how much stimulation it receives from presynaptic neurons.” But in this process of LTP, the Postsynaptic Neuron keeps firing “at an elevated rate” as it has “become more sensitive…to a given stimulus” (Chapter 10). A feature of LTP that carries over into this analysis of MOOCs and learning is one that highlights the role of networked learning pathways as promoted by Hart-Davidson:

“LTP, like learning, is not just dependent on increased stimulation from one particular neuron, but on a repeated stimulus from several sources. It is thought that when a particular stimulus is repeatedly presented, so is a particular circuit of neurons. With repetition, the activation of that circuit results in learning. Recall that the brain is intricately complicated. Rather than a one-to-one line of stimulating neurons, it involves a very complex web of interacting neurons. But it is the molecular changes occurring between these neurons that appear to have global effects.”

Such changes on the “small” scale of an individual brain takes on important nuance when that scale is upsized to “massive” in an online MOOC.

5. How do networks emerge, grow, and/or dissolve?

If the MOOC platform for learning is designed to create new networks of connection among and between student participants, how does that help us better understand the way the pathways to learning are designed? If we interpret network growth in terms of learning, the neurological metaphor offers interesting possibilities for analyzing this in a Composition MOOC. The activity, growth, and nature of the neural system is characterized in terms of Brain Function:

“Basically, the brain works by communication between neurons. There are trillions of neurons in the human brain, and it’s the communication between these neurons that make us feel, think, be able to sense, to actually have consciousness. And it’s this continuing communication between neurons that’s important for processing information. But also, the synaptic connections between neurons in our brain are changing all the time, and it’s this change, or what we call “synaptic plasticity,” or changes in synaptic connections that underlie things like learning and memory, or any response to our environments, so the information we take in is processed” (Unit 10).

These processes of information transfer ideally lead to some form of cognitive permanence in the form of learning and memory. As Hart-Davidson observes, in terms of writing improvement (a sign of learning), “writing improves most for students that spend time revising” (219). Practice makes perfect, we’ve all heard. In the context of neurological network growth, learning means the creation of new pathways and new neurons. In neurobiology, this is referred to as Neuronal Communication / Memory. Neuroscientists study memory creation as well as brain physiology, and assert that the process of learning involves the creation of new networks between neurons. Learning, in other words, changes the brain and the way the nodes interact with other nodes.

Hart-Davidson refers again to Vygotsky’s theories of learning when he argues that the peer-network nature of writing in digital spaces like properly designed MOOCs (i.e., those that follow the many-to-many model) “provide … the ideal conditions for deliberate practice” as a result of the “connectivity” of such networks. Applying the metaphoric terms associated with neuronal communication and memory, such practice could be interpreted in terms of “enhancing certain connections between certain neurons…[to] sculpt out a pathway, a neuronal pathway through this network of neurons” (Chapter 10).

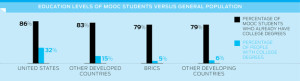

Beyond the basic neurophysiology of learning, this terminology also avails itself to exploring the nature of the MOOC ecology as both massive and open. The sheer number of students involved in the network creates collaborative potential that may not exists in a twenty-person f2f classroom. The variable of experience brought into the classroom also increases with the “open” nature of a MOOC, unrestricted as it is by limits of college tuition or geographical boundaries. Of course, there are other boundaries, such as technological access and / or equitability; however, if the sites built into the MOOC infrastructure are also open (i.e., free) with a reasonable level of operational skill required, this may become less restrictive if one considers that people who are currently opting to take MOOC courses have thus far been demonstrated to be non-traditional students.

There is the opposite to growth, of course. How do MOOCs fail, and what does that tell us about learning in MOOCs? There are numerous voices that weigh in on this: attrition rates are reportedly high for MOOCs, and many are designed with a one-to-many approach which has been proven again and again to be counter-productive for a writing course (Hart-Davidson). Of course, there may also be failure at the node level when students do not participate, thereby stunting the benefits of collaborative peer-to-peer interactivity and, in turn, learning. We see this as well in f2f classroom spaces, even without the “massive,” so how are these concerns about network growth or dissolution addressed if we apply neural network metaphor terms?

Networks grow best when student driven, but the instructor can facilitate these network nodes by creating software / program / virtual locations for such growth (Google Docs, Group Prezis, Discussion Boards, Email). The University of Manitoba’s course “Connectivism and Connective Knowledge,” part of that University’s Certificate in Emerging Technologies for Learning program, is a useful example of a MOOC that utilizes what Hart-Davidson might refer to as the many-to-many approach to learning. New communication nodes that emerge “off the grid” – initiated by students to collaborate (Facebook, email, etc.) – are other ways which a MOOC network may grow and transform in pursuit of learning and connectivity. This might be explored in terms of Neurogenesis, the generation of new neurons. Until recently, neuroscientists believed this process ended by “early childhood,” but recent technological developments have led them to discover that “the brain maintains a reservoir of stem cells that are capable of generating new neurons” (Chapter 10), much like a networked Composition MOOC that encourages “peerlearning” (Hart-Davidson 212).

Networks falter when a MOOC is more xMOOC than cMOOC, a model that relies on the “one-to-many” educational delivery system (video lectures and quizzes and essays) described by Hart-Davidson. Networks may also falter if too little invention authority is granted to students. Some structural integrity (as course design) is needed to prevent a free-for-all and undirected – systems of scaffolding, like neuronal pathways. However, just as neuroscientists have discovered that neuronal networks grow new neuronal pathways as needed in response to new or increased stimuli, the same general metaphor-inspired principle may be applied to explore ways in which MOOCs may facilitate learning. Again, the Manitoba MOOC, and the idea of connectivism as explained here by course co-designer Stephen Downes, may provide a useful example of networked systems of communication and collaboration that illustrate neuronal-like connections designed to foster interactivity and exchange of knowledge to move the learning forward. The premise of an effective many-to-many MOOC course design is to accentuate these individual neural networks and make them part of the learning, not an accessory to it.

Conclusion: MOOCs have been cast by many skeptics (including many composition scholars) as a troubling “break” from traditional models of higher education. However, if seen through the prism of learning models, a Composition MOOC space may instead become one that facilitates creativity and independent thinking by participants who become co-creative powers within a network of learners. The concepts of neurobiology applied as both metaphor and learning theory may facilitate this view.

A limitation of this approach is that the metaphoric image of a neural network isolates the picture into one location. The neural network nodes are a very small part of a much larger system, equated to “a basic cellular mechanism in the brain” (Chapter 10). The dilemma for this application is how this “smallness” can correlate to the “bigness” of a MOOC. Some possibilities have been proposed, but there are other limitations.

What this metaphor does not do – and where an ecology theory might help – is properly explain how this fits into the wider system beyond that of a neural pathway, into the environment that provides the stimuli responsible for neuronal firing and transmission. For a Composition classroom, that might introduce other surfaces beyond the neural pathways and into the realm of stimuli and actions. Syverson asserts that we must see the composition process and students engaged in it as “situated in an ecology, a larger system that includes environmental structures, such as pens, paper, computers, books, telephones, … and other natural and human-constructed features, as well as other complex systems operating at various levels of scale.” Student learning, as Vygotsky might agree, takes place within “a meta-complex system composed of interrelated and interdependent complex systems and their environmental structures and processes” (Syverson 5). The metaphor of neurology does not extend the environment this far.

Finally, comparing the overall efficiency of a neural network to the learning going on in a MOOC reveals several gaps, the most obvious of which are the assumptions we must make in an online space for teaching composition in order to avoid allowing the MOOC to become a glorified test or worksheet bank. Perhaps we need to think about the type of student who might be in a MOOC; why is that student in THAT space? This question as well might be best answered with the additional overlays of such theories as Ecology. In the meantime, however, the neurobiology lens offers interesting ways to connect other scholars and Compositionists in a thoughtful exploration of learning facilitation in networked spaces.

Works Cited:

Binkley, Roberta and Marissa Smith. “Re-Composing Space: Composition’s Rhetorical Geography.” Composition Forum 15 (Spring 2006). Web. 1 Apr. 2014.

Cormier, Dave. “MOOCs as Ecologies – Or – Why I Work On MOOCs.” Dave’s Educational Blog: Education, Post-Structuralism and the Rise of the Machines.” 25 June 2011. Web. 1 Apr. 2014.

Downes, Stephen. Connectivism and Connective Knowledge: Essays on Meaning and Learning Networks. 19 May 2012. Creative Commons. Web. 30 Mar. 2014.

Downes, Stephen. “The Connectivism and Connective Knowledge Course.” Slide Share. 24 Feb. 2009. Web. 30 Mar. 2014. < http://www.slideshare.net/Downes/the-connectivism-and-connective-knowledge-course>

Downes, Stephen and George Siemens. “Connectivism and Connective Knowledge: Getting Started.” MOOC course, University of Manitoba. 2009. Web. 30 Mar. 2014. <http://elearnspace.org/media/GettingStarted/player.html>

Hart-Davidson, Bill. “Learning Many-to-Many: The Best Case for Writing in Digital Environments.” Invasion of the MOOCs: The Promise and Perils of Massive Open Online Courses. Eds. Steven D. Krause and Charles Lowe. Anderson, SC: Parlor Press, 2014.

Syverson, Margaret A. “Introduction.” The Wealth of Reality: An Ecology of Composition. Southern Illinois UP, 1999. 1-27.