Wifi! By Florian Boyd/flickr. Creative Commons license.

The range of selected articles (articles 1, 3, 5, 9, and 11) chosen as the subject of this blog entry come from the site “How Stuff Works?”

First, let’s see what we already know about the “behind the scenes” considerations of WiFi and Mobile technology. Start by taking these two quizzes:

Quiz 1: WiFi – http://computer.howstuffworks.com/wifi-quiz.htm

Quiz 2: Routers – http://computer.howstuffworks.com/router-quiz.htm

**********************************

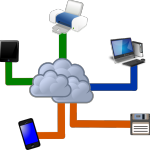

CC openclipart.org

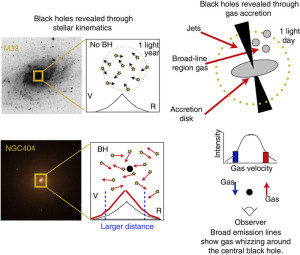

All of these articles make me think of the structural requirements inherent to any network. There must be some system or series of structural conduits through which the connections are made, whether mechanical or organic. The exercise this week emphasizes the reality that we must face when discussing networks – to really analyze or discuss the nature of the network and all of its constituent parts and processes, we must have a fundamental working knowledge of the structure…the “how it works.” Could this be related to what Foucault says about the need to examine discourse by first “freeing them of all the groupings that purport to be … universal unities” in order to reveal or foreground those that are “invisible” (29)? This passage on p. 29 where he describes his reasoning reminded me of an astronomical phenomenon called a “black hole,” the existence of which can only be substantiated by examining relationships, their “reciprocal determination” with regard to other visible spatial bodies, in order to best understand the functioning of said cosmos. Those areas of “difference” (Biesecker) are prime “nodes” for analysis and examination because the action there disrupts the status quo of the established means of interpretation (what we might call a rhetorical canon of practice, perhaps). As WiFi and mobile communication technologies are overtly characterized as network-based means of connectivity, these examples of practical applications of such connections offer us “objects of study” to which we might begin applying our emerging theories.

Here, then, is a brief summary of the articles’ contents, including key terms and definitions drawn from the sources, along with brief observations making connections to our other readings / discussions.

1. “How Are Point-of-Sale Systems Going Mobile?”

A point-of-sale system is, quite simply, that mechanism by which payment is transferred between consumer and sales representative. The article points to the evolution of such systems, from cash transactions to barcodes to SmartPhone apps. The author outlines ways that mobile technology “is altering the way we shop.” Advancements in wireless technology developed in the 1990s allowed data to be transferred even more rapidly, and via mobile devices. Proposed benefits of this technology — factors mentioned in all of these articles — include increased productivity and lower operational costs. Restaurants are the primary node in this development; from mobile card readers to iPhone apps the clients can use to place orders and transfer funds (see the preceding link to a Wall Street Journal article). But questions of security are key. Another device is called “contactless payment,” from computer chips embedded in cards to phone apps, all designed to ultimately speed check out. A white paper published in 2010 highlights this “vanishing checkout lane” phenomenon.

3. “How In-Flight Mobile Phone Services Work.”

Given the recent news stories about banning in-flight cell use, this more recent article (2008) of the set seems particularly interesting. The history of this dates back to 1980s (“the Airfone service…based on radio technology”). The provided explanation begins with a comparison to how cell phones work on the ground, equating cell phone technology to, at most basic, “a two-way radio,” switching frequencies to allow simultaneous back and forth communication. (But it doesn’t go much deeper than that.) However, when airborne, the system relies on different technology: “The service provider, OnAir, uses special equipment to route calls and messages through a satellite network, which patches it into the ground-based network. The airplane crew controls the system and can limit or disable its use.” This again demonstrates a network comprised of several layers of structural networks to allow multiple methods of use.

The article points out safety concerns, especially when the ground-based technology is used when airborne (article refers to this as “traditional ‘terrestrial’ cell phones”). The trouble is based on radio signals, raising the concern that the overlap with airplane navigation signals can cause dangerous disruptions, a concern that seems to be justified given British research reports cited by the Telegraph. But the article also points to a Mythbusters’ episode that challenges this conclusion.

Here’s the technical explanation: “The FCC bans the use of cell phones using the common 800 megahertz frequency, as well as other wireless devices, because of potential interference with the wireless network on the ground. This interference happens as the planes, traveling several hundred miles per hour, leave one “cell” of mobile phone towers and enter a new one quickly.”

5. “How Mobile Broadband Services Work.”

The article begins with an overview of the ravenous appetite we have brought to bear on the internet industry, driving the development of faster & more. Especially significant is the demand for mobile access. A succinct definition of the technology: “Mobile broadband is powered by the same technology that makes cell phones work. It’s all about radio waves and frequencies. Cell phones and cell-phone radio towers send packets of digital information back and forth to each other via radio waves.”

The article describes the two cell network technologies: GSM & CDMA (more common to the US) – “both GSM and CDMA use different algorithms that allow multiple cell phone users to share the same radio frequency without interfering with each other.” MOBILE broadband = labeled as 3G and now 4G (g=generation). CDMA creates separate transmission channels, one for voice, one for data. Access depends on the type of integrated technology owned. GSM uses a network allows for both types, making it more efficient by giving higher priority to download data. Again, special hardware is required to use this type of system, as well as be in range of a signal tower…so there are physical ties to ground-based network mechanics that must be observed.

Here’s a fascinating difference between the time of this article and today: “Cellular providers generally package their mobile broadband services for cell phone users.” With the growth of SmartPhones, this has been reversed (see this 2012 WSJ article ).

9. “How the Airborne Internet Will Work.”

The date for this is particularly problematic, as it now reads like past history, but a search of the internet did reveal more current resources: http://www.airborneinternet.org/aboutus/history/

The author refers to “broadband” or a larger bandwidth for transferring as a “new” means to transmit the heavy loads of data Internet users have come to expect, as a means of replacing the lowly mechanical network hub, the modem, including cable modems, DSL (digital subscriber lines), and now, new options that are airborne. How it works: aircraft-mediated hubs (“High Altitude Long Operation” or HALO) flying in set patterns to accommodate (primarily) business needs for fast transmissions. Other options: blimps or NASA “sub-space” plane (unmanned). Built on the premise that land connections are limited by physics – mechanical restrictions of cables, etc. — the airborne will accelerate transmission time because it isn’t limited by physics of structurality or by physics of space (distance adds time of response).

Here’s where “networks” come into play: the airplanes will exist in numbers, but don’t replace satellites or land lines – rather they are designed to work as part of a system. The “airborne-network hub” that is the airplane itself is designed “to relay data signals from ground stations to your workplace and home computer.”

11. “How Unified Communications Works.”

Defined as tech that allows “messages and data to be rerouted to reach the recipient as quickly as possible,” UC began first with messaging (email, and “other text-based message systems”). UC relies on various “products and tools” that can be made to work together to funnel messages to users when they are away from their computer stations, or, “Communications integrated to optimize business processes” [source: Unified Communications Strategies].”

Businesses rely on UC to reduce costs, increase productivity, and streamline usage. The tech keeps messages from sitting idle on a server somewhere. But there are problems and complications. Some VoIP (Voice over Internet Protocol) services don’t translate seamlessly to consumer’s expectations (based on their experiences with land lines). Another type of communications platform technology used for UC is the SmartPhone. But then there’s the line blurring between the personal and the business uses, including security of data. Still another arena in UC is the cloud – data management. The primary example of successful UC is social media, still “blur[ring] the line[s] between our personal and professional contacts.” This medium advances even more the network potential of UC.

Businesses rely on UC to reduce costs, increase productivity, and streamline usage. The tech keeps messages from sitting idle on a server somewhere. But there are problems and complications. Some VoIP (Voice over Internet Protocol) services don’t translate seamlessly to consumer’s expectations (based on their experiences with land lines). Another type of communications platform technology used for UC is the SmartPhone. But then there’s the line blurring between the personal and the business uses, including security of data. Still another arena in UC is the cloud – data management. The primary example of successful UC is social media, still “blur[ring] the line[s] between our personal and professional contacts.” This medium advances even more the network potential of UC.

13. “How WiFi Works.”

There’s an interesting lapse in the publication date revealed in the opening paragraph, which refers to an enthusiastic prediction that “in the near future, wireless networking may become so widespread that you can access the Internet just about anywhere at any time, without using wires.” Given the WiFi hotspots signs that appear everywhere from Starbucks, to McDonalds, to some gas stations, the dated nature of the article seems almost comical.

From article at www.geeksugar.com

The article describes WiFi as “technology that allows information to travel over the air” using radio waves, comparable in function to “two-way radio communication.” I find it interesting that the article refers to a computer’s capability to “translate” data, akin to the mental processes we take to sift incoming information and produce a version suitable to the purpose and audience (how’s that for rhetorical?).

The router = the node, but not just a center of organization; that node actually “decodes” the input (the language / “signal”), then passes on that info through a physical means (from air to wire). This type of interpretation depends on the mechanical; think of p. 24 Foucault, when he writes that unities of discourse – the accepted methods or systems that comprise a tradition or historical context – are “the result of an operation…[which] is interpretive (since it deciphers, in the text, the transcription of something that it both conceals and manifests” (24).

The reference to “frequencies” makes me wonder if there is a connection to discourses (thinking of Foucault’s comments in Chapter 2). The higher the frequency, the higher the capacity for data. The frequency is described according to “standards” – or accepted nodes – that are described in terms of “coding technique.” It’s all about how much data can be carried. Description of “hotspot” as public nodes of access – seems this terminology may have the potential to be metaphorically useful moving forward in our discussions. (Is that what theory is? A metaphoric framework whereby we take an existing accepted structural system and treat it as an analogy-based means of translating knowledge or data?)

Connections within a network depend on adaptors, computer gear like internal transmitters, and capability to tap into the “standard” transmission lines/radio waves. The computer itself “informs you that [a]…network exists” and requires we exercise intentionality (“ask whether you want to connect to it”). Accessibility depends on identifying / knowledge of the network identification (SSID) – naming that community – access points or channel used by a router, and security (public vs. private) – privileged vs. subversive? One of the authors adds a post script to the article, in which she acknowledges the changes made recently. Of considerable interest are the following comments: “I remember the days when most mere mortals didn’t have modems and couldn’t get on the net, even if they had computers. Perhaps I’m projecting my experiences onto everyone else, but when I was a kid, our computer was this tool we used in isolation.”

Works Cited:

Bonsor, Kevin. “How the Airborne Internet Will Work.” 30 April 2001. HowStuffWorks.com. <http://computer.howstuffworks.com/airborne-internet.htm> 18 January 2014.

Brain, Marshall, Tracy V. Wilson, and Bernadette Johnson. “How WiFi Works.” 30 April 2001. HowStuffWorks.com. <http://computer.howstuffworks.com/wireless-network.htm> 18 January 2014.

Crosby, Tim. “How In-flight Mobile Phone Services Work.” 3 March 2008. HowStuffWorks.com. <http://computer.howstuffworks.com/in-flight-mobile-phone-services.htm> 18 January 2014.

Kelly, John. “How are point-of-sale systems going mobile?” 8 March 2010. HowStuffWorks.com. <http://computer.howstuffworks.com/point-of-sale-mobile.htm> 17 January 2014.

LaPine, Cherise. “How Unified Communications Works.” 9 March 2010. HowStuffWorks.com. <http://computer.howstuffworks.com/unified-communications.htm> 17 January 2014.

Roos, Dave. “How Mobile Broadband Services Work.” 2 April 2008. HowStuffWorks.com. <http://computer.howstuffworks.com/mobile-broadband-service.htm> 18 January 2014.