Spinuzzi, Clay. Tracing Genres through Organizations: A Sociocultural Approach to Information Design. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003.

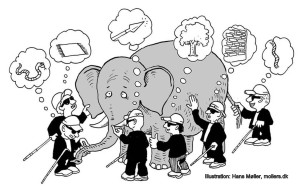

Spinuzzi’s work is a practical application of theory, and as such serves as a fulcrum of sorts on which many of our previous theorists have “play.” Spinuzzi’s book illustrates a methodology which he refers to as “genre tracing,” a means of “examin[ing] how people interact with complex institutions, disciplines, and communities” (23), at times with results not unlike that depicted by the image above. More importantly to our approach to networks (especially those that develop by overlapping existing structures), I believe, is his insistence that this methodology concerns itself with the way workers develop “unofficial…work practices and genres, by adapting old genres to new uses” (23). He advances this method of analysis as a counterpoint to what he refers to as “user-centered design approaches” (x), which he critiques in subsequent chapters as one that creates a “victim narrative” as a way to create binaries of community and actions – in other words, dominant hierarchies. His work provides an interesting illustration of the work we’re doing, combining existing theories to create a new lens, one suitable to a specific object of study: information design. For Spinuzzi, this involves a study of traffic workers, a study that examines both “traditional” means of analysis (the designers at the top of the solution hierarchy) as well as the user-centered “innovative solutions.” Spinuzzi resists choosing one over the other – perhaps what Foucault would refer to as applying a theory of “unities” (26) – and promotes an approach that blends Genre Theory with Activity Theory to information design problems or situations (4).

Spinuzzi’s work explores two competing discourse communities (designers and users), all the while echoing many of the works we’ve read thus far: Bitzer’s systematic rhetorical situation, Foucault’s ideas on unities and irregularities / roles, Popham’s boundary forms and genres, Miller’s and Bazerman’s work with motives and action, the work by Bourelle et al. on digital assessment, Biesecker and relationships, and agency as it relates to localized discourse patterns / needs (which all of our authors thus far have touched upon to one degree or another). Perhaps the most interesting passage, I found, was his integration of Bakhtin’s ideas as they relate to communication practices. The concept of centripetal and centrifugal “impulses” (20) creates a fascinating analogy with which to consider the discourse practices of these two communities: designers and users. His suggestion that the centripetal describes those discourse communities that gravitate toward the “formalization, normalization, regularity, convention, stability, and stasis” – the official line (20) – appears to effectively characterize the sort of knowledge creation privileging Foucault points to in his work. The centrifugal, on the other hand, represents “resistance…, innovation, — and chaos” (20), features that seem more conducive to discussions of agency and the realism of the work place than its counterpart. This passage alone – combined with his list of justifications for using genre tracing as a methodology (22-23) – opens numerous points of connection to our course discussions regarding the ways we envision networks functioning and moving knowledge. This is a rich resource, which will no doubt make its way into my next Case Study.

As a final thought, the tensions Spinuzzi points to brought to mind several images: push-me-pull-you animal from Dr. Doolittle, as well as a very old Abbott and Costello movie – in particular the scene found at time hack 2:00. Both images suggest a unified network of organic origin, often faced with opposing impulses, very much like the average work place.

Abbott and Costello: “Have Badge Will Chase” (1955)