Substance Over Form

The readings this week on Genre Theory (listed below in the Works Cited section) represented a bit of a paradigm shift from the more intense theoretical frameworks of Foucault and Biesecker. And yet… I found myself making both of them a touchstone reference again and again. The concepts of difference and trace, as well as disruptions, etc. returned to mind repeatedly as I read about Miller’s and Bazerman’s attempts to define genre “as a stable classifying subject” (Miller, “Genre” 151), not as a system which derives its definition by focusing on / creating a set of classifying characteristics — in essence, an object. Rather, the works by Miller and Bazerman insist that the most productive and rhetorically viable way to approach the concept of genre is much the same as Foucault and Biesecker — it’s all about the activity, the connections, and the relationships.

The Miller and Bazerman article sets provide both vocabularic underpinnings as well as ways to apply “conceptual and analytic tools” (Bazerman, “Speech Acts” 309). Miller situates the concept of genre as a “stable classifying concept” that is not to be applied as a static form but “on the action it is used to accomplish” (“Genre” 151). This emphasis aligns her with what we’ve read of Foucault, Bitzer, as well as Bazerman, and the turn toward “social action” as the motivating interpretive force behind genre as a tool of analysis. Miller’s “Rhetorical Community” article extends this basic primer by reconsidering her use of the concept of “hierarchy” (68). She reframes her earlier use of the term by applying a new set of concepts: pragmatic or action, syntactic or form, and semantic or what she calls the substance “of our cultural life” (68). She also creates a link with Foucault when she presents genres as “cultural artifact[s]” that can change as cultures evolve (69). Thus, a genre can represent relationships and activities, not simply assessing an inventory of formative characteristics.

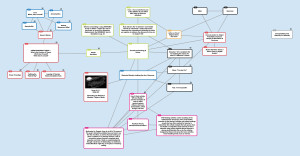

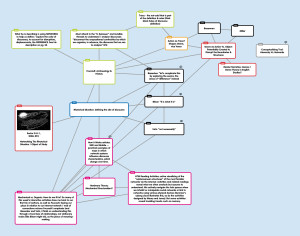

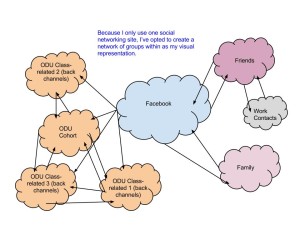

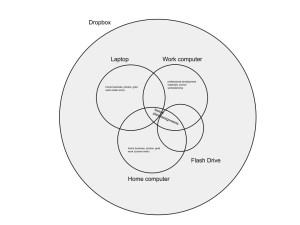

Bazerman‘s article on “Speech Acts” adds a considerable collection of terms to our vocabulary list, contributing such terms as ilocutionary, perlocutionary, and locutionary as analytical concepts that can be used to examine speech acts. “Locutionary” refers to “what was literally stated” — the facts (314). “Ilocutionary” refers to the intended act response of the discursive action (314). “Perlocutionary” then refers to the “actual effect” of the action (315). He establishes a hierarchy into which we can place the relationships between genres, facts, and speech acts — creating a system of nodes, a network that might represent (to Bazerman) “systems of human activity” via discourse (319). In order, this hierarchy builds from “social facts” (312) to “speech acts” (what “words mean and do”) (313), to genres (316) and genre sets (318), on to genre systems (318). These concepts are likely some of the most relevant to our current discussions, as they provide a means of making connections between disciplines or communities in applied situations, to which Popham refers in her article “Forms as Boundary Genres.” Briefly:

- Genre set – “a collection of types of texts someone in a particular role is likely to produce” (318)

- Genre system – “several genre sets of people working together in an organized way, plus the patterned relations in the production, flow, and use of these documents” (318)

- System of Activity – a means to “identify a framework which organizes their work, attention, and accomplishment” (319)

These terms provide us with a means to apply a genre theory as an activity-based (rather than form-based) means to focus “on what people are doing and how texts help [them] do it, rather than on texts as ends in themselves” (319).

In “Systems of Genres,” Bazerman then uses these concepts in an illustrative application of patent forms and the system in which they function to make and shape discursive meaning. His reference to the dangers of allowing our understanding of genres as merely “sediment[ing] into forms” (80) becomes clearer as he walks us through the history of patent systems and their associated texts, demonstrating as he does the activity / formative powers of the genre forms upon the culture and history impacted by this system, creating an understanding of genres as a textual variation of a “speech act” that exists “precisely where langue and parole meet” as an active node site of action (88).

The practical application of genre theory continues in Popham‘s article, which provides the clearest sense yet of how texts (or genres and the communities that use them) can locate a boundary of action — not of object. Her practical analysis of the way medical forms create a boundary space between the medical, scientific, and business communities provides an interesting example of how genre theory, combined with theories of networks and rhetorical situations as we’ve explored thus far, can be successfully applied to real world situations as a means of illuminating those “gaps” or traces to which Foucault refers.

Finally, the online text, Digital Writing Assessment and Evaluation: Forward, Preface, and Afterword, situates our studies within the discipline of higher education and specifically writing studies. In the ancillary chapters, the authors provide the rhetorical situation our field finds itself in: in the midst of the current debate over machine-scoring essays, as well as “what writing is and what it means to write” (Lunsford “Forward”). The emphasis of this work is primarily on “developing … appropriate forms of assessment and evaluation” for digital / multimodal writing (Lunsford), and in doing so situates itself squarely in the midst of our discussion of genre theory and, thanks to the emphasis on digital spaces, network, mechanical, and rhetorical situation theories as well. In short, this collection brings the theory home for those of us engaged in scholarship in English Studies.

Works Cited

Bazerman, Charles. “Speech Acts, Genres, and Activity Sysems; How Texts Organize Activity and People.” What Writing Does and How It Does It: An Introduction to Analyzing Texts and Textual Practices. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 2004. 309-339. Print.

Bazerman, Charles. “Systems of Genre and the Enactment of Social Intentions.” Genre and the New Rhetoric. Eds. Aviva Freddman and Peter Medway. Great Britain: Burgess Science Press, 1994. 79-101. Print.

Bourelle, Tiffany, Sherry Rankins-Robertson, Andrew Bourelle, and Duane Roen. “Assessing Learning in Redesigned Online First-Year Composition Courses.” Digital Writing Assessment and Evaluation. Eds. Heidi A. McKee and Danielle Nicole DeVoss. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press, 2013. Web. 2 Feb. 2014.

McKee, Heidi A., and Dànielle Nicole DeVoss DeVoss, Eds. Digital Writing Assessment & Evaluation. Logan, UT: Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press, 2013. Web. 2 Feb. 2014.

Miller, Carolyn. “Genre As Social Action.” Quarterly Journal of Speech 70 (1984): 151-167. Print.

Miller – “Rhetorical Community: The Cultural Basis of Genre.” Genre and the New Rhetoric. Eds. Aviva Freddman and Peter Medway. Great Britain: Burgess Science Press, 1994. 67-78. Print.

Popham, Susan. “Forms as Boundary Genres in Medicine, Science, and Business.” Journal of Business and Technical Communication 19.3 (2005). 297-303. Print.