First, an aside: I couldn’t stop myself from thinking of this scene from The Wizard of Oz in an entirely new way. While it’s clearly made with the human worldview of home in mind, I began to think of the technology of the sepia tone, the production tools, the stage scenaries and props, a plot filled with concepts of place in terms of time and dreams, the natural (i.e., the tornado). Thanks a lot, Rickert.

I get it. There’s a pattern here; I think I finally see it. When I started reading Rickert’s Ambient Rhetoric, I thought this was a logical next step to our discussions of ecology, ecosystems, affordances, agency, and ANTS, to bring us full circle to Rhetorical Situation where we began. I had no problems buying into Rickert’s premise that the subject-object binary and rhizomatic network pathways so common to discussions of Internet network theories might need some additional theorizing to be really useful. After all, that’s what FrankenTheory building is all about, right? Taking the theories of others and repurposing them or resisting them to fit an application or case study we see as worthy of analysis?

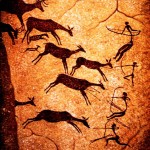

So I enjoyed this text and found innumerable ways to connect it to AND frame our semester’s worth of reading. Rickert’s visit to antiquity – from cave paintings to Aristotle to Plato, to (dare I say it?) the 1970s ambient musician Eno and Microsoft Windows’ early operation system music all created a foundational premise for his argument that was quite engaging. I drank in his discussions of complex systems as evolving environments where – like Deleuze’s rhizome metaphor – the human subject is no longer “all that” given the way our networked lives have evolved to become, well, cyborg like. His discussion of the Earthrise image and the rhetorical nature it reveals, the importance of distinguishing between things and objects – it all really makes sense to me. In fact, I found Rickert articulating so well what I’ve envisioned for many years now: humans and our worldviews err in seeing ourselves through the lens of the “I” for it ignores the almost spiritual balance of existence. I’m avoiding using the words “ecosystem” and “ecology” because Rickert problematizes them in significant ways in Chapter 8, but if delivered through the ambient, these terms may be rendered “safe,” revealing (as he argues) ways these concepts and theorizing “place” as ambient “can be transformative … when it affects our mode of being in the world, making our relationship to the earth not that of subject to depicted object but that of mutually sustaining assemblages of humans and nonhumans fitted into an ecologically modulated world” (218).

I thought of the many movies I’ve watched over the last decade or more with an ecofriendly message – Wall-E, Avatar, Fern Gully, and the one that started it all, Pocahontas – and thought how even the rhetorical moves embedded there remained somewhat human-centered. Even when the messages (as Rickert points out) encourage an eco-consciousness, they still localize the human agency as primary, with rhetoric in persuasive mode rather than a transformative ontological relationship (163).

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pk33dTVHreQ

Even though Pocahontas’ “Color of the Wind” comes close to how I started envisioning Rickert’s approach to ambient rhetoric as “one in which boundaries between subject and object, human and nonhuman, and information and matter dissolve” (1), it soon became clear that it missed one of the features of an ambient rhetoric in terms of how “rhetoric’s comportment toward objects in turn shapes rhetoric itself” (204). As Rickert observes, ambient rhetoric:

- Can’t be separated from “material being,”

- Emerges from the environment,

- This emergence and relationship aren’t simply due to human direction, and

- In “grappling with these entangled, mutually coevolving and transformative interactions among persons, world, and discourses,” we will need “a new appreciation for…their complexity” (163).

In other words, environmental messages miss the mark when it comes to successfully achieving a rhetoric of ambience. I can already see the benefit of this revisioning to comp/rhet, and thought again and again of how this book takes the call to remap the canon of rhetoric made by Prior et al. in a new direction.

Rickert’s journey through Latour, Heidegger, Foucault, and others clearly qualifies as a FrankenTheory, finding and resolving a gap in the scholarship that – by pulling interdisciplinary threads – offers a richer theory. At the heart of this is the object/subject dichotomy and, as he argues, its continued control of our theories and applications of rhetoric. Rickert’s Ambient weaves together theorists of sociology, psychology, classical rhetoric, linguistics, and more as a means of exploring how these often stumble over a continued reliance on this either/or scenario. As the Borg would say, Rickert is taking the “biological and technological distinctiveness” of others’ theories and rhetorical history and adding it to his own to deal with our culture’s (and our field’s) “standard technological quandary where we are either masters of technology or by technology mastered” (204).

His turn to the technological has ramifications for the way MOOCs are currently being theorized as places of learning and places for teaching. His exploration of the image Earthrise as ambient was just the start. His argument that even the network metaphor is insufficient for the task is compelling, pointing out that it still relies heavily on a binary conceptualization of our complex system of inhabiting (122), a flaw he asserts is addressed by his theory of ambience.

While looking for appropriate images to supplement my post this week, I came back across Maury’s recent post on her 3rd case study, which embedded an image from Gibson’s 1979 work on affordances and the visual similar to that on the left. I found these images to be especially productive in terms of thinking of what Rickert was framing in his book on rhetoric and ambience as the “I” centeredness of rhetoric’s history of discourse and meaning (and the way we often continue to theorize rhetoric and networks in a technological era of MOOCs and communications’ technology). Earlier in the term, I considered Latour’s actants as a way to frame discussions about Composition MOOCs, but Rickert layers in Heidegger seem to carry it a step further: “things make claims on us that help constitute not just the various kinds of knowledge we produce but also our very ways of being in the world” (229). In the case of a MOOC, many scholars (who resist dismissing education MOOC technologies as pedagogically blasphemous) would likely agree with this, and certainly Gibson’s theory of affordances would align neatly here. I can see how conceptualizing the online environment of a MOOC as an ambient place, where learning happens not merely at the direction of the human teacher/student, but also when theorized and discussed in terms of ways the diffusion of knowledge through such a complex system must always already be seen in terms of Foucault’s traces. Indeed, at times I wondered in the marginal comments in my book at whether ambient rhetoric is Foucault’s trace metaphor reborn. What would happen if we discussed learning / teaching / collaboration / writing in a MOOC in terms of “dwelling”? How might that open up the discussion about MOOCs as place and the technology’s impact on design as actant / ambient / attunement? In fact, Rickert’s chapter 7 provided me with a host of new ways to discuss the tensions of the place of MOOCs in education. His exploration of the concept of “dwelling” as an “ecological attunement to the environment” (223) may suggest students and teachers (human actants) are less well served when seen through the “worldview” of a God’s eye perspective and its resulting treatment of objects / subjects and their interpretation (224-25). In fact, Rickert’s theory of ambient rhetoric highlights the cultural lens that may have been at the heart of one of my arguments that a “nostalgic” approach to face-to-face pedagogy is at the core of some of our field’s tensions when it comes to online pedagogy practices.

Really, Rickert’s work brought together for me much of our semester’s trajectory. His theorizing is thick with name dropping, clearly demonstrating how to build a FrankenTheory to fill the gaps made visible by those who have come before. Throughout the work, he builds upon Heidegger’s theories of rhetoric in interesting pathways, reinforcing his view that an ambient rhetoric is preferred over traditional rhetoric in the way it becomes “a responsive way of revealing the world for others” (162). His book brought to mind rhizomes and networks, hardware and ANT. For me, even our final mind map took on new meaning as I read his argument that “the complex cannot be…analyzed through…the component elements but rather enters a new state of order … that transcends the initial state” (100). As we watched our mind maps grow in complexity, we might also say we have been“haunted by increasing points of connection but also by their interactive emergence into new forms” (101). Thus, after reading Rickert, I found myself wondering if being asked to reconceptualize and recreate our semester’s worth of work in Popplet might have been the plan all along.

Coda: it seems only appropriate that I conclude my final reading post with a rerun…

Works Cited

Rickert, Thomas. Ambient Rhetoric: The Attunements of Rhetorical Being. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2013.