Donna Haraway has been credited as one of the first to use the term “cyborg” to describe our relationship with the Digital, as we become “hybrids of machine and organism” (151). The field of English Studies, and in particular Composition Studies, has wrestled with theorizing digital space itself as well as the best practices for operating within (and toward) that space, particularly in terms of pedagogy. The scholarship published on this subject in the 1990s, such as that published by Haraway, Selfe, Inman, and others, ranged from discussions of computer interfaces and hardware (Baron) to writing in hypertext (Sosnoski, Johnson-Eilola). The MOOC now extends this discussion in ways that often feel familiar, but create very new spaces in which to theorize composition pedagogical practices and professional tensions.

Donna Haraway has been credited as one of the first to use the term “cyborg” to describe our relationship with the Digital, as we become “hybrids of machine and organism” (151). The field of English Studies, and in particular Composition Studies, has wrestled with theorizing digital space itself as well as the best practices for operating within (and toward) that space, particularly in terms of pedagogy. The scholarship published on this subject in the 1990s, such as that published by Haraway, Selfe, Inman, and others, ranged from discussions of computer interfaces and hardware (Baron) to writing in hypertext (Sosnoski, Johnson-Eilola). The MOOC now extends this discussion in ways that often feel familiar, but create very new spaces in which to theorize composition pedagogical practices and professional tensions.

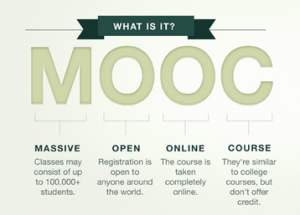

My Object of Study for this course is still MOOCs, or Massive Open Online Courses, designed to teach freshman-level writing. MOOCs, simply defined, are typically tuition- and credit-free classes offered online to any and all interested students, using a variety of methods which include recorded short lectures, discussion boards, and asynchronous activities, depending on the subject matter. There are two distinct “breeds” or genres of mooCs, which might be defined along pedagogical lines: the cMOOC and the xMOOC.

Specifically, I plan to examine Composition MOOCs, as writing courses – especially freshman writing – as problematic areas of study given the established theories of best practices that have evolved in concert with our field’s evolution into digital spaces. The subject matter seems especially useful as an object of study given that many discussions of the online or digital classroom in our field often reflect tensions associated with the history of our field’s quest for professionalization. Given the nature of MOOC-based learning systems, questions of best practices and integrity of degree programs are likely to be part of any network.

The demand for online higher education course offerings comes from a variety of sources and stakeholders. The unique characteristics of MOOCs, however, offer additional challenges, many of which mirror common discussions within our field: assessment, access, instructor training / qualifications, questions of labor, plagiarism, student engagement, retention, and pedagogy. Given recent attention paid to the trend of MOOCs by higher education publications (see resources list below), it would appear that this is an area of debate and activity that may promise productive research.

Thanks to the readings involved in my first two Case Studies, my concept of MOOCs has evolved, especially as I have traced the layers of opposition and possibility represented by the scholarship. The rhetoric of space has emerged as a distinct node in this debate, one which offers possible opportunities for discovery and exploration in terms of theorizing Composition MOOCs.

The underlying foundations of classroom writing practices are framed by physical brick-and-mortar, f2f classroom paradigms. Will the characteristics of MOOCs, framed as they are as “massive” and “open,” challenge those paradigms in a way that demands a reconsideration of our definitions of composition pedagogy? In other words, can we still talk about pedagogy and composition in MOOCs in the same way we talk about them in more traditionally (i.e., f2f spaces) informed classroom spaces? For example, teaching “digital writing” from the perspective of producing texts that will be assessed in a classroom capped at 20 may not share the same features as teaching “digital writing” in a completely digitally interfaced classroom that has no cap at all. Will we then, as Prior et al. argue, need to “remap” the canon of Composition instruction as a result of the pressures brought to bear by this new iteration of networked classroom space? Theorizing this Object of Study in terms of a digitally networked space may help answer such questions.

As I said in my first proposal, given the inherent structural nature of MOOCs, it seems self-evident to approach this Object of Study as a network. However, I believe the network (the rhetorical situation of this study) must incorporate more than the rather obvious element of online connectivity among students and teacher. There is the “incorporeal discourse” of which Foucault writes (24) – and what Biesecker might link to Derrida’s concept of “différance” in discussions of rhetorical situation — which might be explored through consideration of the structural / mechanical, economic / business, as well as pedagogical discourses. In short, the network concept offers a way to connect stakeholder discourses with those of the technical and the pedagogical. Applying a variety of theories to composition MOOCs has provided a deeper sense of the possible, leading to additional ways to think of this object of study as a network and why that may be important to English Studies.

Works Cited

Baron, Dennis. “From Pencils to Pixels: The Stages of Literacy Technologies.” Passions, Pedagogies, and 21st Century Technologies. Eds. Gail E. Hawisher and Cynthia L. Selfe. Logan, UT: Utah State UP, 1999.

Foucault, Michel. The Archaeology of Knowledge and The Discourse on Language. Trans. A. M. Sheridan Smith. New York: Vintage Press, 2010.

Haraway, Donna. Simians, Cyborgs, and Women. London: Routledge. 1991.

Johnson-Eilola, Johndan. Nostalgic Angels: Rearticulating Hypertext Writing. Norwood, NJ: Ablex Publishing, 1997.

Jones, Sherry and Daniel Singer. “Composition On A New Scale: Game Studies and Massive Open Online Composition.” CCCC 2014.

Sosnoski, James. “Hyper-Readers and Their Reading Engines.” Passions, Pedagogies, and 21st Century Technologies. Eds. Gail E. Hawisher and Cynthia L. Selfe. Logan, UT: Utah State UP, 1999.

Resources:

1. NY Times article Nov. 2012

2. Educause resource list

http://www.educause.edu/library/massive-open-online-course-mooc

3. Businessweek article Jan. 2014

4. Duke Univ. Coursera Comp I course page

https://www.coursera.org/course/composition

5. Blog written by a participant in the above

6. Georgia Institute of Tech Comp MOOC course page

https://www.coursera.org/course/gtcomp

7. Academe blog: “The Gates Foundation and Three Composition Blogs”: http://academeblog.org/2012/12/03/courage/

8. The Chronicle of Higher Education – “What You Need to Know About MOOCs.” Frequently updated hub of articles: http://chronicle.com/article/What-You-Need-to-Know-About/133475/

9. “What Is A MOOC?” EdTechReview. Image and video. 15 March 2013.